What is Accessibility?

Accessibility means designing learning materials, courses, and experiences so that all students can participate fully and equitably. It recognizes that neurodiversity and disability are natural parts of human variation, and that every learner brings valuable strengths, abilities, and ways of engaging to our classrooms.

Why does this matter?

When we design with accessibility in mind, we can proactively remove barriers that might limit participation and create learning environments that support the success of all students.

|

Legal and Institutional Commitments: Accessibility is a legal responsibility and a teaching value. |

From Accommodations to Accessibility

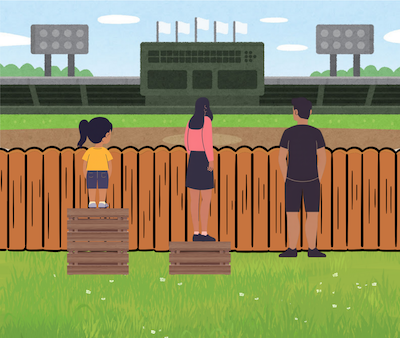

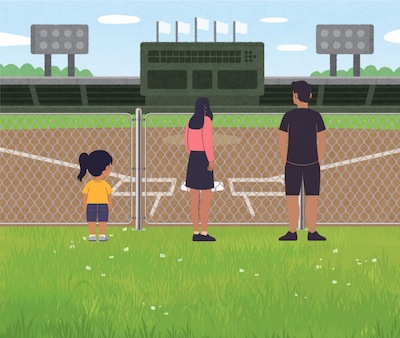

While individual accommodations are often necessary to remove barriers to learning (by reactively adjusting materials or experiences to meet the needs of specific students), accessibility means designing learning environments that work well for everyone from the start.

|

Inaccessible design excludes people by introducing barriers at the outset. |

Accommodations remove existing barriers for whomever is there at the moment, but often require extra or reactive work. |

Accessible design is a proactive approach that gives full access to all currently and in the future, without extra or reactive work. |

| Above images recreated by Serena Assie, GMCTL, University of Saskatchewan Source: UW-Madison (Accessibility) and U-Minnesota (ODA). Based upon an idea first shared by Craig Froehle. |

||

This proactive approach aligns with Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a framework that helps educators create flexible, engaging learning experiences by offering multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression. In practice, this might include:

- using clear headings and readable text structure to make materials easy to navigate,

- adding alternative text for images and describing visuals shared in class,

- captioning videos, providing transcripts, and ensuring multimedia content is useable by different types of learners,

- creating documents and files that are screen-reader friendly and easy to access,

- fostering participation options that offer multiple, flexible ways for students to engage in learning activities, and

- designing assessments that provide diverse options for students to demonstrate their learning.

By utilizing UDL to design course materials and learning experiences with accessibility in mind, we can remove barriers to learning before students ever have to encounter them.

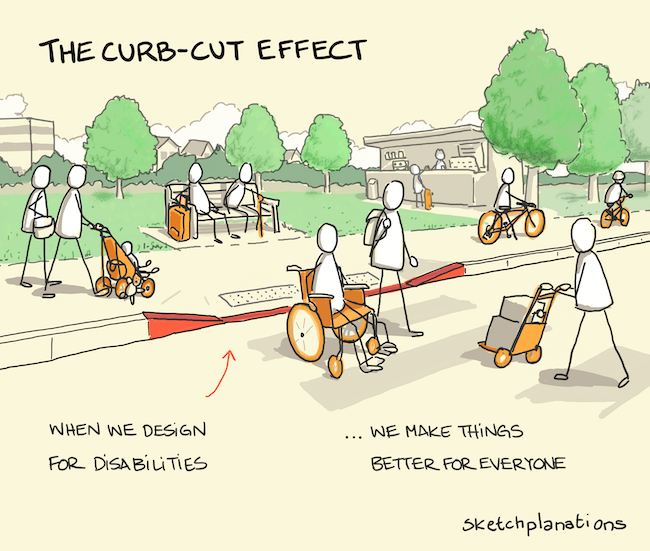

Designing for Everyone

This approach also reflects what is known as the "curb cut effect." Curb cuts were originally designed to help wheelchair users navigate sidewalks but quickly proved beneficial to everyone – from parents with strollers to travelers with rolling luggage. This is a great example of universal design in practice.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and accessibility practices build on that same idea, but with intentionality – designing from the outset to meet diverse needs and reduce barriers before they arise. For example:

- Captions support not only students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, but also those studying in noisy environments or learning in an additional language.

- Clear document structure helps both screen reader users and also those scanning for key points.

- Offering multiple ways to participate (such as discussions, reflections, or collaborative projects) helps to support different strengths and abilities amongst learners.

- Designing assessments with diverse options allows students more ways to successfully demonstrate their learning using varied formats (such as writing, presentations, or applied projects).

When we design learning with accessibility in mind, we make courses that are better for everyone and elevate learning for all by reducing friction and opening multiple pathways to success!

Accessibility as a Shared and Ongoing Responsibility

It’s important to note that building for accessibility is everyone’s responsibility – not just specialists or support units. Small, intentional choices by individual educators can make a big difference.

Accessibility is also a journey of continuous improvement. By reflecting on our teaching approaches, revising our materials, and learning from student feedback, we can continually reduce barriers to participation and create more inclusive, equitable experiences for everyone at USask.

In the resources that follow, you’ll find practical guidelines for creating accessible learning materials, strategies for fostering inclusive and flexible teaching practices, and links to USask-specific supports and further learning opportunities to help you put accessibility into action.

Building Blocks for Accessible Learning Materials

Creating accessible course materials ensures that all students can use, navigate, and understand the content you share. These building blocks and the more-specific guidelines within them provide a foundation for creating webpages, documents, slides, and media that are more accessible for all users, removing barriers to participation and upholding USask commitments to inclusive learning environments for all. These guidelines are based upon WCAG 2.0, the international standard for digital accessibility.

Explore the sections below on how to meet these guidelines. Download this summary document to keep on hand: USask Guidelines for Accessible Learning Materials.Summary:

Using correct headings, simple fonts, and descriptive hyperlinks makes course content easier to read, navigate, and understand – especially for students using screen readers or students who are deaf, hard-of-hearing, or who process auditory information in diverse ways. Proper tagging of headings (i.e., using tools in Word, Canvas, or HTML) also aids in creating a clear page structure, which makes your materials more accessible to all learners.

Guidelines:

- Properly tag headings (h1-h6) and use them in the correct hierarchy.

- Avoid using bold or italicized text in place of a proper heading.

- Avoid using small fonts.

- Use simple, familiar fonts.

- Underline linked text, only.

- Ensure link text makes sense out of context.

- Avoid using URLs as anchor text.

For more information, see Headings, Fonts, and Hyperlinks

Summary:

Tables and lists can make course content easier to scan and understand, but they need to be created properly to be accessible. For tables, this means adding captions, tagging headers, and keeping layouts simple. For lists, always use the built-in list tools (bulleted or numbered) rather than typing symbols manually. These steps ensure screen readers can interpret and convey the information clearly for all learners.

Guidelines:

- Create table captions.

- Tag table headers.

- Keep tables simple.

- Use the proper list type for your content.

- Do not simply type bullets or numbers in place of a proper list.

For more information, see Tables and Lists

Summary:

Thoughtful use of colour, contrast, and white space can make your course materials more readable and engaging for all students. To ensure accessibility, don’t rely on colour alone to convey meaning, make sure text and background colours have strong contrast, and keep layouts uncluttered with plenty of white space. These simple practices improve legibility, supporting diverse cognitive processing needs, and support learners with colour blindness, low vision, or cognitive disabilities.

Guidelines:

- Don’t use colour, alone, to convey concepts.

- Ensure link colour is distinct from surrounding text colour.

- Use a contrast of 7:1 for text and background colours.

- Use sufficient white space.

For more information, see Colour, Contrast, and White Space

Summary:

Mathematical content must be accessible to all students, including those using screen readers or requiring high-contrast displays. Use dedicated math editors (like Canvas or Word Equation tools) whenever possible, provide alt text for images of equations, and consider offering audio recordings to read equations aloud. These practices ensure that formulas are readable, scalable, and understandable for every learner.

Guidelines:

- Build equations using dedicated math editor tools (like the Canvas Math Equation tool).

- Write alt text for images of equations.

- Record audio files reading equations.

For more information, see Formulas and Mathematical Expressions

Summary:

Images can enhance learning, but students who are blind or low vision need descriptive alternatives to access their meaning. Always add alt text for images that convey content, keep descriptions concise, avoid redundancy, and provide extended explanations elsewhere for complex visuals. Decorative images can be marked as such, ensuring accessibility tools focus on meaningful content.

Guidelines:

- Add alt text to any image that is not decorative.

- Leave out unnecessary information from alt text.

- Avoid redundancy in alt text.

- Keep alt text concise, when possible.

- End alt text with a period.

- When images are too complex for concise alt text, include your description elsewhere.

For more information, see Images and Alt Text

Summary:

Audio and video can enhance learning, but they must be accessible to students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, students learning in an additional language, and those with limited bandwidth. Providing accurate captions and detailed transcripts ensures all students can access spoken content and important audio cues, while also supporting diverse learning needs. When using auto-generated captions and transcripts, be sure to check them for accuracy before sharing.

Guidelines:

- Create accurate captions for video content.

- Create detailed transcripts for multimedia content.

For more information, see Multimedia (Audio & Video)

Effective Practices for Accessible Teaching

Accessibility isn’t just about the materials we share – it also depends on how we teach. The following list of effective practices highlights everyday things you can do in your teaching – like offering flexibility, clear communication, and inclusive assessment – that will help to create learning environments where all students can fully participate and demonstrate their learning.

Explore each section below for details on how to apply these practices.Clear, consistent communication helps all students understand expectations and navigate the course confidently. Provide agendas, instructions, and announcements in plain language, post online materials in a predictable location, and use multiple formats (written and verbal) to convey key information.

For more information, see:

Flexibility with assignment due dates can support students’ diverse needs and – when clearly structured – still maintain accountability. Whenever reasonable, build in a deadline structure that allows for extensions, alternative timelines, or buffer periods. This allows you to strike a balance between maintaining course requirements and meeting the institution's duty to accommodate. Providing options for how assessments are weighted in your course can also aid in making a more accessible and inclusive learning experience, while offering a greater degree of student autonomy in learning.

For more information, see:

Providing students with meaningful options for how they engage in your course fosters motivation, ownership, and deeper learning. Choice can include different modes of participation (e.g., discussion, online posts, group vs. individual work) and multiple ways to demonstrate learning through assignments. Also important is inviting student voice by welcoming their input on course activities, assessments, or learning processes, which helps you to create a more inclusive and responsive classroom environment.

For more information, see:

Effective assessment, as outlined in the USask Assessment Principles, supports learning when it is transparent, scaffolded, and designed to optimize student success. This means providing multiple opportunities for students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills, using a variety of formats, and sequencing tasks to build skills over time. Avoid over-reliance on high-stakes or less accessible methods (e.g., timed exams), and instead design assessments that reflect meaningful learning outcomes, emphasize authentic, real-world applications, and allow students to demonstrate their learning in a variety of ways.

For more information, see:

A physically and socially inclusive classroom environment supports all students by removing barriers and fostering mutual respect, including respect for diversity across prohibited grounds of discrimination. That includes things like using microphones, describing visuals, and addressing participation barriers such as room setup or group dynamics. It also includes supporting students holistically through meaningful actions like land acknowledgements, use of preferred pronouns, being mindful of exam scheduling around religious or cultural observances, and connecting students with campus services (wellness, academic, and career) that help them thrive.

For more information, see:

Embedding accessibility into your course policies signals a commitment to inclusive learning. Clearly outline your accessibility commitments in the syllabus, explaining how students can connect with Access and Equity Services (AES) to access supports and how you will collaborate with them to ensure their learning needs are met. This provides you with an early opportunity to reinforce respect for diverse learning needs as a course norm.

For more information, see:

Some teaching practices are adopted with good intentions but can unintentionally introduce barriers to accessibility. For example, strategies aimed at exam security – like relying heavily on timed in-class exams, using image-based exam questions rather than text, or certain types of virtual proctoring approaches – may prevent some learners from fully participating. Similarly, the use of digital tools intended to enrich engagement can create challenges if those tools are not compatible with assistive technologies. While these strategies may serve a purpose at times, it’s important to weigh their potential impacts on accessibility and ensure that all students have equitable opportunities to learn and demonstrate their knowledge.

For more information, see:

Digital Tools for Accessibility

At USask, there are several tools available to help instructors design accessible materials, and for students to access content in ways that work best for them. Explore each section below for some recommended tools and features, divided into tools primarily useful for instructors and for students.

- Canvas Accessibility Checker – Built directly into the Canvas editor, this tool identifies common accessibility issues (e.g., missing alt text, low contrast, table formatting) and guides you to fix them. It helps ensure your course content is more usable for all students.

- Microsoft Office Accessibility Checker – Available in Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, and Excel, this feature reviews documents for accessibility issues and provides recommendations. Using it before sharing your files ensures materials are screen-reader friendly and easier to navigate.

- Automatic Captioning in Panopto – USask’s preferred video tool can generate captions automatically, which can then be edited for accuracy as needed. Captions are essential for students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, but benefit all learners by providing another option for how to engage with recorded lectures.

- Canvas Immersive Reader – Allows students to have Canvas pages read aloud, adjust text size and spacing, and change background color to support diverse reading and comprehension needs.

- Canvas User Account Settings – Provides options to switch to a high-contrast user interface (UI) or a dyslexia-friendly font, making the platform work for a greater variety of learner needs and preferences.

- Read&Write – This free downloadable software offers a literacy support tool that reads text aloud, highlights as it reads, and offers assistance with writing, vocabulary, and study skills. This software empowers students, including those with dyslexia or other learning differences, to engage more confidently with reading and writing tasks.

- Microsoft Learning Tools – A set of features built into a variety of Microsoft products (including Word), these tools allow students to listen to text, dictate their own writing, or transcribe speech into notes, making study and assignment prep more flexible.

Resources and Links

USask supports

Accessibility in teaching is supported by a range of practical tools, campus services, and guiding frameworks. Find resources, supports, learning opportunities, and key legislation and standards that can help you design courses where all students can thrive.

- Access and Equity Services (AES): A resource for faculty on implementing accessibility and equity measures in teaching, and supporting student accomodations.

- Universal Design for Learning - One Small Step: Online guide that introduces UDL principles through small, manageable strategies, including chapters on creating universally-designed assessments and best practices for technology-enabled learning.

- Accessible Scanning - University Library: The Library Scan Request service provides digital copies of print materials in accessible formats, ensuring that PDFs are properly tagged and readable by assistive technology.

- Online Course Review - Gwenna Moss Centre (GMCTL): Online courses can be reviewed by an experienced Instructional Designer against a set of quality criteria, including accessibility standards.

- SaskOER Network Pressbooks Authoring Guide: Checklist for Accessibility This checklist can be used to ensure the accessibility of a resource being created or adapted in Pressbooks.

| Learn More |

|

| Relevant Legislation & Standards |

|

Get support

For support or a consultation on this topic, reach out to the team at the Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching and Learning.