Place and Culture

The Story of Pinehouse

Pinehouse Community and Visit

The GMCTL, Rose Roberts and Maria Campbell, travelled to Pinehouse during the annual Elders’ Gathering in June of 2018. The community of Pinehouse has hosted the Elders Gathering since 2010; elders from across northern Saskatchewan gather for a week of kīyokīwin to share traditional activities, knowledge and reconnecting. This profile of Pinehouse was developed through kīyokīwin and specific interviews with the following Elders and Community Leaders:

Rosa

RosaTinker

Frank

FrankNatomagan

Yvonne

YvonneMaurice

Ida

IdaRatt

Caroline

CarolineRatt-Misponas

Samuel

SamuelMisponas

These conversations were held in whichever language the interviewee was most comfortable, Cree or English. We offer their stories as they were gifted to us for you to learn about and better understand the people and place of Pinehouse. We hope that hearing the stories in Cree, with translations provided by Rose Roberts, that you are able to get a sense of why this community is loved by its people. In addition to these personal stories we offer a more Western description of the Pinehouse Story developed by the Indigenous Voices team.

(If there are any errors or misrepresentation, we are wholly responsible.

Please contact us and we will make any corrections.)

The Story of Pinehouse

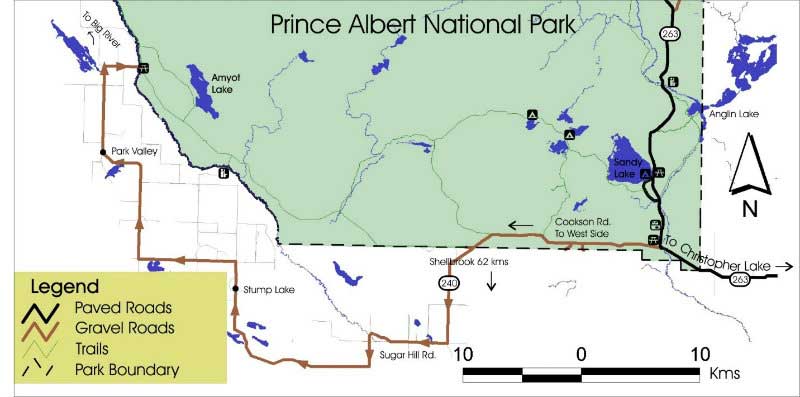

The community of Pinehouse, with a population of approximately 1500 Metis/Cree members, lies along the westerly shoreline of Minahikowāskahikan Sāhkahikan, known also as Pinehouse Lake. The lake was originally known as Kinīpihko-sāhkahikan (Snake Lake) to the local Cree and Metis inhabitants.

Prior to the 20th century, Pinehouse Lake was inhabited by members of the Denesuline Nation who practiced their traditional lifestyle of fishing, trapping, and hunting in the area. During the height of the fur trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) operated a trading post from 1875-1939 along Apakosīs Sīpi (Mouse River, also known as Souris River, French for mouse), now renamed and known as Belanger River on maps. Belanger River was located in the traditional territories of the Dene, Cree and Métis peoples. As a result of the fur-trade and no immunity to European diseases, a smallpox outbreak in 1901-02 nearly decimated the Dene population, forcing many of the survivors out of the area (McNab, 1992). Consequently, smaller groups of Cree and Métis families from surrounding areas began moving in, creating small settlements in areas near Kinosew Sīpi (Fish River), Black Bear Island Lake, and Apakosīs Sīpi. The Saskatchewan 1906 Census indicates there were 73 people living in the area that was called Souris River on the Churchill.

In their stories Elders from Pinehouse state that no one lived in the area where the village is now located. There was a trapper’s cabin there but it was only used as an overnight or short term stay by the trapper. The village of Pinehouse came to existence through a series of events related to missionization, resource extraction and the Natural Resources Transfer Acts, 1930. These Acts, one for each province (e.g., Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta) allowed the federal government the transfer of jurisdiction that it had exercised over the crown lands and natural resources to the provincial governments (Hall, 2006).There is no unanimous agreement or official documents of the precise date when the Village of Pinehouse was established, but it is generally thought to have been settled somewhere between 1940-1950. These dates incorporate the building of the Church (1944), the building of the school (1948), and the introduction of the CCF socialist policy.

Gold, uranium, and other minerals were the target of mining industries and with more European settlers pushing north, the provincial government sought more control over economic development activities occurring in the area. In an attempt to alleviate problems emerging from the expropriation and exploitation of Indigenous lands and resources, the Saskatchewan government under socialist leader Tommy Douglas (Thomas Clement Douglas) and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) implemented several economic policies and conservation practices which further hindered the ability of Indigenous peoples to sustain their social, cultural, and economic ways of life. As a result of the above policies, many Dene, Cree, and Metis families living on traplines throughout the northern part of the province were forcefully relocated, including the families that lived in the Pinehouse Lake area.

Pinehouse existed under a different name (e.g., Snake Lake settlement) until 1954 when it was officially recognized as a village and renamed Pinehouse. Elder Samuel Misponas stated that they didn’t like the sound of Snake Lake so they changed it to Pinehouse Lake; while he didn’t explicitly state who they were, it was understood to mean the provincial government. The lack of clarity about a settlement date is related to government policies about how Indigenous communities were categorized. A division of judiciary and fiduciary obligations exist for Metis and First Nations communities, Metis being under provincial jurisdiction whereas the First Nations are under federal jurisdiction. Therefore, many communities were documented separately.

The Catholic Church was built in 1944, and brought people to the area, helping to form the community of Pinehouse. Caroline Ratt stated her parents came to Pinehouse to get married in the church and ended up settling in the village. Another important development was the establishment of the school. Even though most people were maintaining traditional lifestyles and had an untraditional perspective on the role of education, the provincial government (i.e., Tommy Douglas and the CCF) forced people to adapt to Euro-western education through policies of mandatory education. An elementary school was built in 1948, but oral history states that education was not a priority for many Pinehouse families, who continued to follow their traditional land based economies.

Despite the resilience of the traditional way of hunting and trapping that continued into the 1960s, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) promoted government policies to limit or prevent this local independence. Through enforced conservation policies for fishing and trapping, communities like Pinehouse were forced to give up traditional ways of living and accepted practices that did not promote a thriving economy. The importance of educating their children was reinforced, however, with only the elementary school in the Village, families were forced to send their children to other communities including residential schools for secondary school. Grades 7- 9 were added in 1970, but it was not until 1995 that a student could go from Kindergarten to Grade 12 in the community.

The Metis community of Pinehouse actively tried to resist the DNR policies. The regulations to prevent exploitation of natural resources were incorporated into industries for the local population, such as the fishing industry. However, in the 1970s the fishing plant was shut down and the Department of Northern Saskatchewan (DNS) housing program closed, causing socio-economic challenges for the community. Over time, people were forced to become more dependent on the social services industry while coping with poor housing, limited access to education and job opportunities. These deplorable conditions lead to addiction issues for those who had no hope for a positive future. Eventually the situation in Pinehouse drew the attention of CBC’s 5th Estate who portrayed the unflattering reality of the community in an exposé called The Dry Road Back in 1979. This became a wakeup call for the community, who took advantage of the coincidental development of uranium mines in northern Saskatchewan, to improve their situation. The construction of an all-weather road in 1979, built primarily for access to the Key Lake uranium mine, provided positive changes for Pinehouse by decreasing the isolation and dependency on air charters. Employment opportunities within the mining sector and related industries provided the Village with hope for a better future.

Despite the negative government policies developed and implemented without consultation and support from local communities, the families of Pinehouse had and continue to have a strong feeling of bonding based on the traditional beliefs of reciprocity, family ties and connection between all living things. As described in the Pinehouse Elders’ stories, mutual respect, hard work, and support for all the members of the community and the land helped them get through difficult times. Wahkohtowin is a Cree word that is often translated into kinship but it encompasses many facets of the Indigenous worldview including the concepts described above.

The community’s practice of traditional ways of hunting, fishing, and trapping was an important factor for survival. This northern village has a strong Metis/Cree worldview, which is embedded in the local economy and contributed to the development opportunities.

Despite the relocation of many families in the 1940s, despite not having any voice in the Northern Resource Transfer Acts or in the development of the resource extraction industry, and despite changes to policies restricting hunting, trapping and fishing lifestyles, Pinehouse has become a strong and proud Metis/Cree community. The community members are indivisibly connected to their culture and language, which has helped them to endure and develop their resilience. Elders and knowledge keepers share their stories and emphasize the importance of helping each other in order to persevere. The Village of Pinehouse with the majority of people identifying as Metis - continues to support an Indigenous worldview based on community, reciprocity and living with the land.

The story of Pinehouse describes a community that was forced into existence, but that has become a real home for so many of its people. Their history is one of belonging and a shared worldview and commitment to their own social, cultural, and economic survival.

Please watch the following videos for a fuller audiovisual experience of The Story of Pinehouse:

Caroline Ratt-Misponas

Elder Samuel Misponas: Trapping and Moose Hunting

Relocation

Stories from Our Land The Story of Pinehouse The Story of Stanley Mission

Afterword Check Your Knowledge Reflection

Bibliography

Gulig, A. G. (2002). "Determined to Burn off the Entire Country": Prospectors, Caribou, and the Denesuliné in Northern Saskatchewan, 1900-1940. American Indian Quarterly 26(3), 335-359.

Hall, D. J. (2006, February 7). Natural Resources Transfer Acts 1930. Retrieved from The Canadian Encyclopedia: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/natural-resources-transfer-acts-1930

McNab, M. A. (1992). Persistence and Change in a Northern Saskatchewan Trapping Community. Retrieved from University of Saskatchewan: https://harvest.usask.ca/bitstream/handle/10388/5840/McNab_Miriam_Arlene_1992_sec.pdf

Province Saskatchewan District 17 Saskatchewan North Sub-District No.1. (1906, August 22-23). Retrieved from Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, 1906: http://sites.rootsweb.com/~cansk/census/SaskatchewanNorth-1-32.html

Raymond, D. M. (2013). The Metis work ethic and the impacts of CCF policy on the Northwestern Saskatchewan Trapping Economy, 1930-1960. Retrieved from University of Saskatchewan: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.825.3731&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Saskatchewan Sound Archives Programme. (1976, September 4). Transcript of an interview with Albert E. Broome conducted by Murray Dobbin . Retrieved from Indian History Film Project: https://ourspace.uregina.ca/bitstream/handle/10294/886/IH-352.pdf

University of Saskatchewan. (n.d.). Pinehouse Lake Aerial Photographs 1970-1979 . Retrieved from Sask History Online: http://saskhistoryonline.ca/islandora/object/pahkisimon%3A357

Commitment to their social, cultural, and economic survival

"I would like to see our future, our future generations working like us, working to build the community, working to build family ties, working to build infrastructure. Working, maybe to even have a road into the community where we’re not eating dust. But it’s coming, these are the blueprints that we want to make for them, this is what we’d like to see as elders, when they start taking care of us that’s what we want to see. We want you to build from what we teach you." -Ida Ratt