Place and Culture

Introduction

Introduction

The importance of land, of place, of belonging to a certain locality is of paramount importance when it comes to understanding and appreciating Indigenous worldview and culture. First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples are intimately connected to the land, as are many Indigenous peoples around the world. Being able to survive and thrive as humans, as families and as communities depended on a deep and thorough knowledge of the land, the waters, the animals and the plants; the surrounding environment in its totality. When one has grown up in a harsh and sometimes hostile environment, there is an ingrained respect for the land, the weather and the animals that inhabit the same space.

This is in comparison to the Eurowestern worldview of using the land and waters for a purpose, such as farming, mining and other forms of resource extraction. Changing the surrounding environment to meet the needs of the person, family, and community is commonplace and expected. Purchasing, selling and owning the land is also a central tenet to the belief system. Eurowestern worldview operates within a hierarchical structure, and humans are at the top of the hierarchy, everything else in creation is there for them to access and use. The one who owns the most land is also the richest and at the top of the hierarchy, land is seen as a source of economic gain.

Whereas, Indigenous peoples believe that they belong to the land, the land does not belong to them. Kikawinow aski (Cree for Mother Earth) - all Indigenous peoples share a similar phrase in their own traditional language – encompasses not only the land but also the waters, the air, and the clouds. And similar to how babies relate and depend on their mother, so do Indigenous peoples relate and depend on kikawinow aski.

Some philosophical underpinnings of land based peoples include: relationships, observation, reciprocity, locality and oral transfer of knowledge.

- Relationship is a complex concept within Indigenous worldview, it is a deep understanding of the term ‘everything is related’. Relationship is not only the relationship between humans, it is also the relationship with the rest of creation, the animals, the land, the waters and Creator. Indigenous people live in relationship with everything around them, with humility and respect. This is in contrast to Western hierarchical perspectives where men/women live at the top of the food chain, and everything below lives in relation to them. Indigenous worldview encompasses the belief that the Earth is animate, that the waters are animate, that the rocks are animate. As Leroy Littlebear states: If everything is animate, then everything has spirit and knowledge. If everything has spirit and knowledge, then all are like me. If all are like me, then all are my relations.(1)

- Observation is the initial method of teaching among many Indigenous Peoples. One learned by watching, until one reached a certain age when they were given the opportunity for hands on experience. Since many of the activities were related to day-to-day survival, this method was useful in many ways including waiting until one had the fine motor skills required to handle axes, knives, needles and other tools. Having to watch also honed one’s observation skills, a necessity when one is living in nature – which can be a dangerous place to be for the uninitiated. When one lives in relation to everything, then everything around one becomes a teacher for them. First, the relationship must be observed, then honoured and respected, then appreciated (aka, learned from).

- Reciprocity is one of the Natural Laws followed by the majority of Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island. One does not take anything from the earth without providing something in return. Since we live in relation to everything, we practice and maintain humility and respect, which we do through continuous reciprocity with everything. For example when one harvests medicines, they say a prayer of gratitude and place tobacco in the area where the medicines were taken from. Reciprocity also applies to human interactions. Members in a community often had specific skills and gifts, for example, a midwife would help a woman with birthing, the family would pay her with gifts.

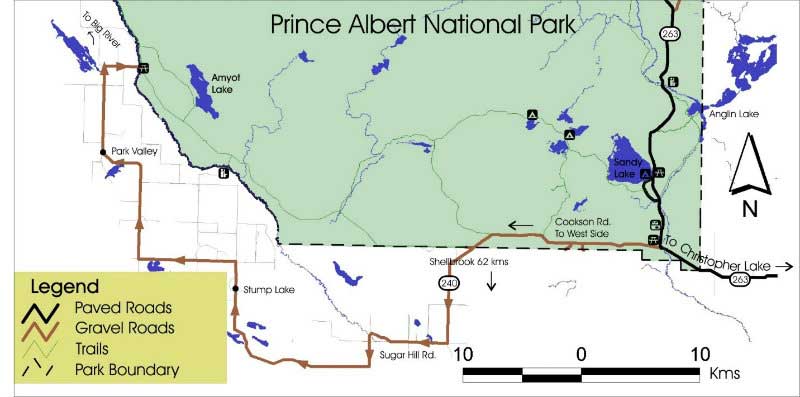

- Locality in relation to place and space is that over time Indigenous peoples develop land based knowledge about their specific territory. One’s identity is explicitly tied to their territory, and this knowledge is passed on through language. The place names of areas, the significance of those names, of plants and their uses, of animals, seasons, weather patterns; all are necessary to survive within a certain area and that knowledge isn’t necessarily transferrable to another area. Having relationship with place and everything that exists there creates an interactive intimacy and attachment to place, much like some people are attached to their mothers and don’t stray far.

- Oral transfer of knowledge is the primary method used by many Indigenous Peoples. Having a relationship with everything, includes knowledge. The importance of this rests in the commitment to oral traditions despite written modes, because written modes of communication are stripped of relationship elements. When you have a living relationship with knowledge, your understanding of it delves deeper than the objective truth and provides shades and nuances that sometimes transcend and other times don’t transcend places, seasons, people, gender, etc. The importance of language in naming place was already mentioned, the oral tradition necessitates a complex language system in order to capture all the nuances found within nature. A well known example is that of Inuit words for snow; there are 12 words to describe snow and 10 words to describe ice in Inuktitut.(2) Inuit have to have many ways of naming these two phenomena as they are an integral aspect of their environment. The transfer of knowledge is part of every day activities. Language and culture is often learned from the mother and everyday contact within a family setting. The stories and meaning-making of place are part of the child’s education, and Elders as keepers of knowledge are the teachers.

The Elders are the caretakers, nurturers, developers, etc. of the relationships Indigenous peoples have with everything. Elders also believe it is their responsibility to be caretakers of the land; this process plays out in the everyday rituals and activities of living close to the land, and fostering an attitude of humility and deference. As the knowledge keepers of the communities, the Elders share their knowledge by showing and by role-modelling the relationship everyone needs to establish with the Earth.

Land based traditional knowledge is a component of culture. Culture is the values and beliefs that a People use to understand and function in the world. This culture manifests itself in a People’s language, customs, foods, religion/spirituality, music, arts and other characteristics that define a certain group of people (Hofstede, 2001). Land based peoples’ lives revolve around the land, the waters, the animals and all components therein; thus their culture is defined by the land. Place and culture are inextricably intertwined, one cannot survive without the other.

To honour the Indigenous communities of Saskatchewan and their local knowledge, we made trips to the communities and interviewed Elders, Knowledge Keepers and leaders on how their communities came into being. We asked them to share their stories of their homes, their places and what keeps them there; in their words and their languages. These are their histories of place and culture and the truth of how they came to be where they are.

Stories from Our Land The Story of Pinehouse The Story of Stanley Mission

Afterword Check Your Knowledge Reflection

(1). Littlebear, Leroy (2000). Jagged Worldviews Colliding.

http://www.learnalberta.ca/content/aswt/worldviews/documents/jagged_worldviews_colliding.pdf

(2). The Canadian Encyclopedia. (2019). Inuktitut Words for Snow and Ice.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuktitut-words-for-snow-and-ice

(3). Hofstede, G. (2001), Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Commitment to their social, cultural, and economic survival

"I would like to see our future, our future generations working like us, working to build the community, working to build family ties, working to build infrastructure. Working, maybe to even have a road into the community where we’re not eating dust. But it’s coming, these are the blueprints that we want to make for them, this is what we’d like to see as elders, when they start taking care of us that’s what we want to see. We want you to build from what we teach you." -Ida Ratt