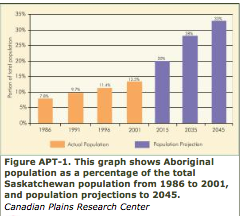

There are several different ways of defining the Indigenous population: by national census data, Indigenous and Northern Affairs (INAC) data (the Indian Register), health data, band rolls, membership in the Métis Nation—Saskatchewan, etc. Census data count Indigenous population in at least three ways: self-identification (as Registered Indian, non-status Indian, Métis, Inuit, or undifferentiated Indigenous); claimed Indigenous ancestry (single or multiple responses); and people who are officially counted as Registered Indians. In the 2001 census, 130,190 residents of Saskatchewan self-identified as Indigenous (13.5% of the total population of the province) (see Figure APT-1). Of these, 83,745 (64.3%) claimed to be only “North American Indian” (First Nation); 43,695 (33.5%) to be only Métis, and 235 only Inuit; while another 895 claimed more than one type of Indigenous identity (likely First Nation and Métis) and 1,620 some other sort of Indigenous identification. Examining data for people claiming Indigenous origin, however, one can note that a slightly larger number of Saskatchewan residents (135,035) claimed to be wholly or partially of Indigenous descent. Of these, 70,390 (52.1%) were only of “North American Indian” origin, and another 24,045 (17.8%) partially; 12,480 (9.2%) were solely of Métis descent, compared to 19,880 (14.7%) who were partially so; 7,860 (5.8%) claimed other multiple Indigenous origins; and 150 respondents claimed to be only Inuit, plus another 235 partly Inuit. The count of Registered Indians again provided different data: 84,075 divided almost equally between those living on reserve (43,715) and off reserve (40,365). In fact, there has been progressive urbanization of the entire Indigenous population in Saskatchewan, with close to half (46.7%) now living in urban areas.

Saskatchewan now accounts for 13.3% of the total Indigenous population of Canada, including about 15% of both the Registered Indian and Métis populations. In absolute numbers, Saskatchewan currently ranks fifth for the province having the largest number of Indigenous residents; however, proportionate to the total provincial population it is ranked first or second (comparable to Manitoba). The Indigenous and Registered Indian populations of Saskatchewan have grown rapidly: the Indigenous identity population grew to 111,245 in 1996—twice what it had been in 1971—and, as already noted, to 130,190 in 2001. This rapid growth may be largely attributed to the fact that the estimated total fertility rate among Registered Indian women is higher in Saskatchewan (3.1 in 1996) than any other province or territory, while the regional patterns for both Métis and Non-Status Indians are similar. This growth is somewhat countered, however, by Indigenous mortality rates which, while declining, are still higher than in the non-Indigenous population. Certain illnesses and causes of death are still multiple times higher among Indigenous people in Saskatchewan than non-Indigenous: pneumonia has long been a prominent factor in neonatal, infant, and child mortality; deaths by fire, suicide, drug and alcohol abuse, and accidental poisoning have been more prominent among Indigenous youth; and diabetes, circulatory and respiratory system diseases, and motor vehicle accidents have ranked above the provincial norm, especially for Registered Indians on reserve.

On the whole, the Indigenous population of Saskatchewan is much younger than the non-Indigenous: 49.9% (in 2001) is under 20, compared to just 26.5% of the non-Indigenous population; only 3.2% is over 65 years of age, compared to 15.9% of the non-Indigenous population. While a large number of young Indigenous people will soon be entering the labour force, their occupational diversity will depend on educational levels attained. On the one hand, the proportion of Indigenous people aged 15 and above who have had less than high school education (52.6% in 2001) is disproportionately large compared to the non-Indigenous population (37.8%). On the other hand, the proportion of Indigenous people with a university education, trades or other higher education (39.3%) has been rapidly increasing. Today, close to 10% of the total student body at the University of Saskatchewan is Indigenous. Opportunities for higher education have multiplied for Indigenous students, as evidenced in increasing enrolments at the First Nations University of Canada (Regina and Saskatoon) and the Saskatchewan Indian Institute of Technologies (Saskatoon).

Although it lags behind the non-Indigenous population in certain respects, the occupational diversity of the Indigenous population will be improving. Compared with non-Indigenous, the Indigenous labour force is proportionately over-represented in construction (8.2% compared to 5.2%), sales and service (30.8% compared to 22.8%), and trades (19.0% compared to 14.4%); but still somewhat under-represented in finance and insurance (1.6% compared to 3.9%), real estate (1.1% compared to 1.3%), management (6.4% compared to 8.6%), business, finance and administration (12.0% compared to 15.1%), and primary industry (8.1% compared to 16.5%); and seriously under-represented in other occupational categories. The unemployment rate for the potential non-Indigenous labour force in Saskatchewan was 4.8% in 2001, whereas among the potentialIndigenous labour force it was 23.0%, among First Nations 29.4%, and among Métis 15.5%. On-reserve average individual income has been increasing, yet it has consistently lagged behind off-reserve, particularly urban. While the gap betweenIndigenous and non-Indigenous incomes has been gradually closing, the former still remain well behind the latter.

Alan Anderson