During World War I (1914–18) and World War II (1939–45), thousands of Indigenous men and women voluntarily enlisted in Canada’s armed forces. They served in units with other Canadians, fought in every theatre in which Canadian forces took part, and more than 500 status Indian servicemen lost their lives on foreign battlefields. An estimated 800 men and women from First Nations in Saskatchewan served during the World Wars and in Korea. Although reliable statistics are not available, the official record lists more than 100 status Indians from Saskatchewan who served during World War I, including over half of the eligible adult males on the Cote Reserve. Overseas, Indigenous soldiers were recognized as effective snipers and scouts, endowed with courage, stamina, and keen observation powers.

At home, Saskatchewan Indians also donated $17,257.90 in support of the war effort—almost double that of any other province. The File Hills community alone raised $8,562 for the Red Cross and Patriotic Funds, while Indigenous women formed Red Cross societies, organized patriotic leagues, sewed, and knitted socks and sweaters for the troops overseas. The school children of Gordon’s reserve knitted seventy-five pairs of socks and raised money for the Belgian Relief and Soldier’s Tobacco Funds. A serious issue arose about the federal Military Service Act (1917), which conscripted Canadians for overseas service: although there is no reference to military service in any of the written treaties, oral assurances recorded during negotiations for Treaties 3, 6, 8 and 11 promised that Indians would not be forced to serve in foreign wars. After

The Department of Indian Affairs trumpeted the achievements of status Indians at war’s end. And in 1920 Edward Ahenakew could proclaim: “Now that peace has been declared, the Indians of Canada may look with just pride upon the part played by them in the Great War, both at home and on the field of battle. Not in vain did our young men die in a strange land; not in vain are our Indian bones mingled with the soil of a foreign land for the first time since the world began.” Exposure to the broader world changed veterans profoundly—but they returned to the same patronizing society they had left. Inequitable veterans’ settlement packages disadvantaged many First Nation

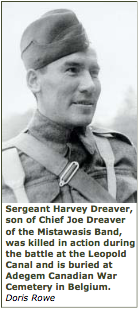

Despite interwar discontent, Saskatchewan’s Indigenous peoples again answered the call during World War II. More than 440 Saskatchewan Indians enlisted for military service in this conflict (including at least 22 women), with the highest enlistments from the Carlton, Crooked Lakes, and File Hills agencies. Twenty-seven of these soldiers were killed or wounded. Overall, Indigenous enlistments from Saskatchewan were undoubtedly higher than these figures because Non-Status Indians and Métis were not differentiated from non-Indigenous Canadians. On the home front, women’s service clubs and community groups again raised funds for the Red Cross and other war charities. Indian Affairs records indicate that many donations went directly to local organisations, and that “substantial donations of furs, clothing and other articles were made, the monetary value of which has not been calculated.” The difficult question of Indian conscription also arose; while the federal government did not grant a blanket exemption to Indians during World War II, liberal exemption policies ensured that few if any Indigenous conscripts were sent overseas.

Indigenous servicemen and women had again fought overseas as

In recent years, Indigenous Veterans have received

P. Whitney Lackenbauer