By: Blair Stonechild

The Indigenous peoples of Saskatchewan have inhabited this region for approximately 11,000 years, during which time they established self-sustaining societies. Contact with Europeans brought with it external cultural and economic forces that would dramatically affect the lives of Indigenous people; their story has been one of adaptation and survival. During the 235 years of Fur Trade contact (1670–1905), challenges included devastating epidemics and depletion of wildlife resources; after Canadian annexation of the North-West Territories, Indigenous people were subjected to government policies that sought to erode their identity and rights. Today, they are recovering many of their rights, rebuilding their societies, and seeking to play a meaningful role in contemporary Canada.

European contact resulted in the common use of First Nations names that were different from the way they referred to themselves. The proper self-ascribed names of the First Nations of Saskatchewan are as follows: Nêhiyawak1 (Plains Cree), Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux), Nakota (Assiniboine), Dakota and Lakota (Sioux), and Denesuline (Dene/Chipewyan). The term “First Nations” is preferred to the misnomer “Indian,” and is generally used except where the latter is required in

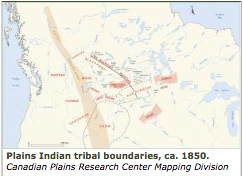

The original tribal distributions were significantly different from the pattern of Indigenous occupation of the region today. The first White man to reach the interior of the northern plains, Henry Kelsey, led by Nakota and Nêhiyawak guides in 1690, reported that much of present-day southern Saskatchewan area was occupied by the Atsina, (also called Gros Ventres), as well as the Nakota and Hidatsa to the southeast and the Shoshone (also called Snake) in the southwest. To the north, the area between the forks of the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers and to the west was occupied by the Blackfoot.6 The Chipewyan, a branch of the Dene, occupied areas of the northern boreal forest. The advent of the fur trade brought about dramatic changes in territorial distributions as these First Nations groups entered into competition and conflict over fur resources.

The First Peoples

Indigenous hunter-gatherers are believed to have entered the northern plains following the retreat of the last glacier, approximately 11,000 years ago. Around 9000 BC, there is archaeological evidence of the spread of hunters using fluted spear points to hunt bison. Archaeologist James V. Wright theorizes that eastern Early Archaic peoples migrated to the western plains around 6000 BC, where they came into contact with the Plano peoples.2 By 3000 BC, there is evidence of organized Bison hunts on the northern plains, using more advanced spear points with distinctive rippled flaking.3 These ancestral peoples laid the basis of the tribal cultures that were found at the time of European contact.

First Nations traditional cultures were based upon ideologies in which humans formed a part

Relations during the Fur Trade

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) established its first fur trade post at York Factory on the shores of Hudson Bay in 1670 and named its trading territory, all of the lands draining into Hudson Bay, Rupert’s Land.7 A typical First Nation trader could bring in a hundred beaver pelts, with which he could purchase necessities such as a gun and ammunition, kettles, knives, traps, and blankets. Once the necessities were purchased, he could buy luxury goods such as tobacco, beads or liquor. The introduction of iron trade goods dramatically affected Indigenous lifestyles, diverting much of their efforts from traditional seasonal activities to an economy based upon the harvesting of furs and bartering of trade goods to First Nations in the interior. The Nakota, whose prior habitation on the prairies eased territorial access for their Nêhiyawak trading allies, acted with the latter as middlemen who bartered trade goods for furs. The Blackfoot became early beneficiaries of trade, and with the acquisition of guns were able to drive away their adversaries, including the Shoshone and Kootenay.8 During this period, changes in lifestyle and intertribal relations occurred as First Nations sought to use newly introduced technologies to their advantage; First Nations and fur traders also developed a relatively peaceful relationship based on reciprocal dependence, in which each side would come to the other’s aid in times of need.

By the 1730s, the Cree were beginning to reside permanently on the plains, and this led to the development of a distinct tribal entity: the Nêhiyawak (Plains Cree).9 The Blackfoot had a valuable commodity to trade to the Nakota and Nêhiyawak: horses, which had been spreading northward after being first introduced to Central America by the Spanish.10 Despite limited equipment, First Nations became highly skilled horse riders: this, combined with the use of guns, enabled them to wield unprecedented influence. By 1787, the ruthless trading practices used by the Nakota and Nêhiyawak contributed to the breakdown of friendly relations with the Blackfoot.11 The vanquishing of their mutual enemies, the Shoshone, Gros Ventres and Kootenay, not only removed a common foe but deprived these tribes of a vital social function: the opportunity for young warriors to go on raiding parties in order to prove their valour. In this changed cultural landscape former allies became rivals, and over the next century, the raiding between Nakota-Nêhiyawak and Blackfoot became legendary.

With the end of their alliance with the Blackfoot in 1787, the Nakota-Nêhiyawak alliance turned to the Mandan Nation’s trading centre, located on the upper Missouri River, for horses. With no other providers of guns and other trade goods to compete with, the Nakota and Nêhiyawak enjoyed a tremendously strong trading position,12 which was further strengthened when the Nahkawininiwak (Saulteaux or Plains Ojibway),13 who traded goods originating from Montreal via the Great Lakes, joined the Nakota and Nêhiyawak. This came to be known as the Iron Alliance, the term reflecting the trade in iron goods upon which their power was built.14 The Alliance’s influence at the Mandan trading centre waned after American sources of trade goods became available around 1805.15

The Métis, mixed-blood descendants of marriages between French fur traders and First Nations women, had come to play an important role in the trading network of the North West Company (NWC), which was established in 1779 and threatened the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trade monopoly.16 Increasingly hostile relations between these two companies would eventually lead to their forced merger in 1821. When the HBC established the Selkirk Colony, consisting of Scottish farmers, to introduce agriculture to Rupert’s Land, this was viewed as a threat to the NWC supply route: the Métis confronted the settlers at Seven Oaks in 1816 and killed twenty, an event that has been heralded as the birth of Métis nationalism. Over the next five decades, the Métis increased in numbers, becoming the dominant population of Red River and enjoying an economic power based upon the trade of buffalo products to the United States market.17

Almost two centuries of the fur trade, however, were beginning to take their toll on the land and the people. Epidemics, in particular, smallpox, were the greatest single killer of First Nations: the major epidemics, recorded in 1780, 1819, 1838 and 1869, carried away over half of the population each time, the Métis being affected to a lesser degree.18 The effects of such events on the social, political and economic well-being were traumatic. Fur trade resources began to decline noticeably, first on the eastern prairies with the beaver by the 1820s and the buffalo by the 1850s.19 In the 1820s, missionaries began to appear in Rupert’s Land, and First Nations youths such as Charles Pratt were recruited to attend the first mission school at Red River. Other leaders such as Ahtahkakoop welcomed missionaries—not only for their new religious ideas but also because of the reading, writing and arithmetic skills they could impart.20 Missions were established earlier in the north: for example, the church at Stanley Mission, constructed in 1854, is the oldest existing building in the province.

As the fur trade declined, interest in the agricultural potential of the northern prairies began to be explored by the Palliser and Hind Expeditions of 1859. First Nations faced increasing hardship due to the decline of their middleman role in the fur trade and to increasing intertribal conflict over dwindling herds of buffalo. However, as the fur trade drew to a close, the First Nations retained a strong sense of their own cultural identity, as well as a firm attachment to the land which had often been acquired through protracted intertribal struggle. The Nakota, Nêhiyawak and Nahkawininiwak of the Iron Alliance, and to a lesser extent the Métis, were forming through intermarriage a new hybrid culture loosely based upon Nakota material culture, Nêhiyawak language, and Nahkawininiwak spirituality. This legacy can be seen in the mixed tribal compositions that are found in today’s First Nations.21

The Numbered Treaties with Canada

One of the earliest initiatives of the

Canada’s strategy in approaching treaty negotiations had been to attempt to arrange a straight land transaction

First Nations responded to the emerging starvation crisis of the 1880s by organizing political meetings. Piapot, one of the principal leaders of Treaty 4, organized a meeting at Pasqua Reserve, and Treaty 6 chiefs Big Bear29 and Poundmaker organized gatherings to air Treaty grievances in 1884.30 The federal government, believing that such activities were worthless and only led to trouble, used North-West Mounted Police intervention and deprivation of rations to disrupt these activities; such responses resulted in near-violent confrontations on the Sakimay and Poundmaker reserves in 1884. The First Nations’ political strategy sought to avoid violence, opting instead to organize a broad-based political movement in Treaties 4, 6 and 7, which would present a unified voice to Ottawa.31

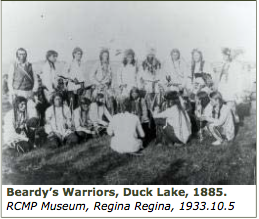

North-West Resistance of 1885

Frustrated by the lack of progress in addressing their concerns, the Métis of the Batoche area, supported by local settlers, approached Louis Riel, then living in Montana, to lead their cause. Riel, having had some success in forcing the federal government to meet Métis demands in 1870, declared again the establishment of a Provisional Government on March 19, 1885. The only group that had not provided political support for his plans, which by this time radically called for the establishment of a New Papacy, were the First Nations. However, due to a series of circumstances beyond their control, First Nations quickly became mired in the events of the North-West Resistance of 1885.32

After the Resistance was quelled through the use of military force, the federal government quickly convicted 19 Métis and 33 Indians of

Policy of Assimilation

Residential schools, which were not mentioned during treaty discussions, became the federal government’s primary tool with respect to the assimilation of Indigenous people.35 The Social Darwinist belief popularly held by Canadians at the time was that Indian cultures were inferior and therefore should be replaced by British culture. First Nations children, who were the most vulnerable to influence, were removed from contact with their parents and communities to the greatest extent possible. As Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, then Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, explained:

When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with its parents, who are savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly impressed upon myself, as head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.36

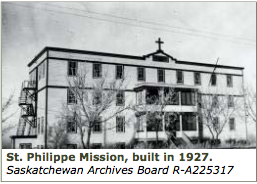

Indian industrial schools were initially established in 1883 at Lebret, Battleford, and High River.37 Other schools, such as the Regina Indian Industrial School in 1890, were established at the initiative of religious denominations. More common were less costly boarding schools, which offered less in the way of training programs and were closer to their communities but still isolated the children from their families.

Residential schools soon proved to be expensive and ineffective. Zealous religious denominations, competing for converts, built too many schools. Meanwhile, enrollments were falling due to high student mortality rates caused by tuberculosis and other diseases. The denigration of their culture, homesickness, and an unimaginative curriculum resulted in a deplorable education experience, and some tried to escape. Children who finally returned to their communities found themselves alienated from both Indian and White societies. Altogether, fourteen residential schools were built in Saskatchewan.38

The creation in 1905 of the province of Saskatchewan, named after the Cree term for “fast flowing river,” led to a boom in land speculation. A policy emerged around this time aimed at the erosion of First Nations land through the securing of Indian reserve land surrenders. While First Nations viewed their reserves as permanent homelands for their descendants, surrenders became very appealing to land speculators and government officials, who believed that the Indian population would continue to decline. Reserve lands could only be lost through a majority vote in favour of the surrender taken under the Indian Act, a piece of legislation intended to manage every aspect of First Nations life. First Nation reluctance was overcome through fraudulent dealings often involving bureaucrats at the highest levels, and by the use of coercion such as cutting off rations and offering inducements of immediate large cash payments. As a result of these actions, close to half of Indian Reserve lands in southern Saskatchewan were surrendered between 1896 and 1920.39

The influence of Indian agents over Indian reserves was pervasive: these individuals held total control and their authority displaced that of chiefs, many of whom had been deposed by the federal government. The agents controlled the ability of Indians to travel out of the reserve, and nothing could be bought or sold without their permission. Under the Indian Act, agents possessed broad judicial powers enabling them to lay and adjudicate charges without recourse to appeal. First Nations resistance attempted to organize politically: at a meeting on the Thunderchild Reserve in 1921, the League of Indians of Western Canada was formed, led by John Tootoosis.40 Other organizations, such as the Allied Tribes representing Qu’Appelle area bands, were also formed.

Post-War Period

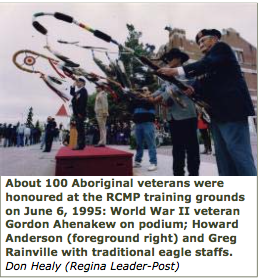

Uncertainty set in during the 1930s and 1940s as Indian policy was generally viewed as being a failure and no new directions were emerging. Following the end of World War II, pressure came from Indigenous Veterans, who had volunteered in higher proportion than the general population and become sensitized to the need to be freed from oppression.41 In 1951, the Indian Act was revised, removing some of the most archaic aspects of the old regime such as employing Indian agents. First Nations individuals were allowed to leave the reserve, although it was not until 1960 that they were granted the right to vote federally by the Diefenbaker government and could begin to enjoy the privileges of ordinary citizenship. The Hawthorne Report, a national survey of the social conditions of Indians conducted in 1963, revealed that Saskatchewan Indians were among the most poverty-stricken in Canada.42

Contemporary Indigenous Peoples of Saskatchewan

Category Definitions

According to the current Canadian constitution, “Aboriginal Peoples” includes “Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.”45 Treaty Indians are listed as members of First Nations who are descendants of the signatories to one of the Numbered Treaties. Non-Treaty Indians are members of First Nations, primarily the Dakota, who have reserves and are recognized as having Indian Status under the Indian Act, but were not signatories to treaties. The term “First Nations” has become commonplace following the assertion of Aboriginal political rights in the 1980s. Non-Status Indians are those First Nations who for varying reasons never signed treaties nor fell under the jurisdiction of the Indian Act. The Métis are descendants of French fathers who participated in the fur trade and of First Nation mothers and are generally identified with origins in the Red River area. The descendants of British fathers and Aboriginal mothers have historically been referred to as half-breeds.46

Of the Indigenous Languages, Nêhiyawêwin (Cree language), part of the Algonquian language group, is the most commonly spoken in Saskatchewan, with about 20,000 speakers. Nahkawêwin (Saulteaux language), primarily spoken on eleven First Nations mainly in southeastern Saskatchewan, is the westernmost dialect of the Ojibway language. Nakota, Dakota and Lakota are dialects of the Siouan language found mainly in the United States, but only a few fluent speakers of the latter two languages remain in Saskatchewan. There are approximately 5,100 speakers of Dene, most of whom are found in northern Saskatchewan. Michif is the unique language of the Métis, created through the blending of French and Cree words. The teaching of Indigenous languages in First Nations and provincial schools is becoming commonplace.

Indigenous Demographics

The

Politics and Governance

The announcement of the Trudeau government’s Indian Policy of 1969, which advocated termination of Indian treaties, rights and reserves, galvanized the First Nations of Canada to organize nationally under the National Indian Brotherhood (NIB).49 The rejection of the Canadian government’s assimilation policy signalled the first major shift in Indian policy since Confederation and ushered in the contemporary period, marked by the recovery of culture, rights, and self-determination. The NIB’s first president was Walter Deiter of the Peepeekisis Reserve.50 Other national leaders of the NIB from Saskatchewan included David Ahenakew and Noel Starblanket. Following the rejection of the 1969 policy, the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians turned its efforts toward the recovery of Treaty Rights, including redress of Indian land claims. Leaders of the provincial political organization have included Sol Sanderson, Roland Crowe, and Perry Bellegarde.

In 1982, the Federation of Saskatchewan Indians entered into a political convention that acknowledged the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations as representing the collective interests of the province’s First Nations, each of which continued to retain its inherent sovereignty. This transformation was consistent with the enhanced recognition of Aboriginal rights entrenched in the Canada Act of 1982. The First Nations Governance structure includes Tribal Councils—regional groupings of First Nations set up for advisory and program delivery purposes.

The focus of First Nations political activity, apart from the reclamation and protection of rights, has been the building of capacities for self-determination: for example, an agreement signed by the Meadow Lake Tribal Council with the governments of Canada and Saskatchewan acknowledges the First Nations’ inherent right to self-government.51 While First Nations are still heavily dependent on government transfer agreements, increasing emphasis is being placed on facilitating the creation of band and individual enterprises, as well as promoting greater involvement in the mainstream economy through post-secondary training and creation of employment opportunities. The Department of Indian Affairs allocates annually about $600 million for First Nations programs and services such as governance, education, housing, and economic development.

The Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC), created in 1989, is a unique approach devised in Saskatchewan to resolve issues surrounding Treaty Land Entitlement. The OTC was given a new mandate in 1996 to educate the general public about why treaty rights exist, and how those rights affect the general public. The Office convenes discussion tables to bring First Nations and the federal government to consider Treaty implementation measures in areas such as education, health, and justice. The province participates as an observer.52

Métis and Non-status Indians

The first provincial organization to unite the Métis of northern and southern Saskatchewan was the Métis Society of Saskatchewan, formed in 1967. Under the leadership of Jim Sinclair, non-status Indian issues came to be included in 1975 under the umbrella of the Association of Métis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan (see Non-Status Indians). Following the recognition of the Métis as an Aboriginal people under the Canadian Constitution in 1982, focus returned to the Métis achieving rights and self-determination; the new political organization was named the Métis Nation–Saskatchewan.

While most continue to live in historical Métis communities such as Lebret, Willow Bunch, Duck Lake, St. Louis, Green Lake and Buffalo Narrows, where some Métis Farms are located, the Métis are becoming an increasingly urbanized people. Métis and Non-Status Indian legal issues have received greater attention, particularly since the inclusion of the former as an “Aboriginal people” in Canada’s 1982 Constitution; of special concern are hunting and fishing rights, and setting aside a dedicated land base. The lack of a distinct Métis land base, apart from Métis farms, has presented great challenges to the preservation of a sense of community, as individuals commonly assimilate into the mainstream. Enumeration of the Métis population is a central issue since no official lists have been kept historically. Mixed-blood peoples other than the Métis, such as those descended from Scottish fathers and Aboriginal mothers and historically referred to as half-breeds, as well as Non-Status Indians, who are culturally Aboriginal but are not recognized by the federal government, are represented by the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples.53

Political pressure for recognition of Métis rights, applied by individuals such as Harry Daniels and Clément Chartier, resulted in their recognition as an Aboriginal people under the Constitution Act of 1982: there is now a Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians, whose role is to help to reaffirm the unique position of these peoples in Canada.

Indigenous-Provincial relations

Treaty Indians were initially hesitant to engage in provincial politics, fearing that it would lead to loss of treaty rights and assimilation; however, they received some reassurance when the CCF government of T.C. Douglas granted them the provincial vote in 1960.54 Presently, First Nations Intergovernmental Relations exist primarily with the federal government; the latter provided all entitlements, including those traditionally under provincial jurisdiction such as education and health. Saskatchewan played a key role in Indian policy with the Natural Resources Transfer Agreement (1930), in which the province was obligated to respect Indian hunting and fishing rights, and to provide provincial Crown lands if required for the creation of Indian reserve lands.

Provinces have hesitated to become involved in Indian policy because of the enormous costs involved in dealing with Indigenous needs, which have become increasingly focused on urban issues of poverty, crime, adoptions, and family services. In Saskatchewan, the Department of First Nations and Métis Relations coordinates the province’s dealings with Indigenous issues and programs. Increasingly, Indigenous people such as former Cabinet Minister Keith Goulet are becoming involved in provincial politics.

Education

Residential schools began to be phased out in 1965 and were replaced by an imposed Joint School Agreements system, under which seats were purchased in local mainstream schools; but this policy failed because of racism and an inappropriate curriculum, and was discontinued.55 The adoption by the federal government of the Indian Control of Indian Education policy in 1973 led to the construction of First Nations-controlled education facilities on the reserves. There was, up until the time of the CCF government in the 1940s, uncertainty about the administration of Métis affairs: the federal government had left the issue to the provinces, while the provinces expected the federal government to become involved.56 This was particularly true in education, as both the provincial and federal governments rejected responsibility for Métis issues such as education, which resulted in phenomena such as the “road allowance people.”

Responding to the high Indigenous dropout rates, the Saskatchewan Education Department began to develop and institute an accredited Kindergarten to Grade 12 Native Studies curriculum that respects Indigenous cultures, heritage, and rights.57 Such changes are designed to eradicate the ignorance that underpins much of the racism that exists today. Reforms to the provincial curriculum in the mid-1980s have helped to provide, for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students, accurate and culturally reaffirming portrayals of Indigenous conditions and aspirations. Today, First Nations children have the choice of attending one of approximately 100 elementary and high schools located on reserves or to attend a local provincial school. Given the expansion of reserve youth numbers and the decline of rural populations, non-Indigenous students sometimes attend reserve schools, a startling reversal from a few decades ago.

In the area of post-secondary education, the Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Centre (originally the Saskatchewan Indian Cultural College), founded in 1972, was mandated to promote the preservation of Indian culture through the production of a curriculum as well as other activities. Based in Regina, with sub-campuses in Saskatoon and Prince Albert, the First Nations University of Canada (formerly the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College), founded in 1976, has a provincial, national and international mandate to meet the higher-education needs of Indigenous peoples. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is an example of a unique subject being taught that is relevant to modern issues—in this case, the environment. As of 2004, the institution had graduated over 2,500 students. The Saskatchewan Indian Institute of Technologies (formerly the Saskatchewan Indian Community College), founded in 1976, has the mandate of providing post-secondary education in areas other than academic.

Similarly, the Métis Nation-Saskatchewan has established institutions such as the Gabriel Dumont Institute, which mounts higher education programs such as the Saskatchewan Urban Native Teachers Education Program (SUNTEP) and offers post-secondary training of a technical nature.

Health Issues

In the recent past, treatment for diseases such as tuberculosis has been instrumental in improving Indigenous Health.58 The nature of illness among Indigenous peoples has been changing: diabetes and AIDS have emerged as major contemporary challenges. The well-being of Indigenous people lags behind mainstream society, with infant mortality nearly twice and diabetes four times the national rate. The First Nations and Inuit Branch of Health Canada funds community health clinics on reserves, as well as at Indian hospitals such as those at Fort Qu’Appelle and Battleford.

Land Management and Claims

Challenges faced include finding improved ways to manage land and capital, strengthening of human resource capabilities, and diversification of the economy including greater integration with the surrounding areas. Reserve lands are held communally by the First Nations, although individual families have occupancy rights to use specific areas. The fact that lands cannot be sold places obstacles to raising capital, which may require land as collateral; under the Indian Act property is not taxable, and First Nations members cannot be sued.59

There are different categories of First Nations Land Claims. Land surrenders denote the removal of portions of land from reserves that already existed. Although First Nations viewed reserve lands as

Land entitlement

Economic Development

The lack of an adequate economic base has been one of the most serious problems facing Saskatchewan First Nations. Indian agriculture has historically been a failure because of defects in government policies involving inadequate land management approaches and insufficient support for modernization of technology; as a result, agriculture has not proven to be the economic salvation that was promised under the treaties. Today, the economy of the reserves remains largely dependent on government transfer payments: opportunities remain few and unemployment remains high.

Successful First Nations Economic Development today is increasingly globalized; examples are the Kitsaki Development Corporation, as well as various Indian urban satellite reserves such as the McKnight

Today Indigenous business is one of the most rapidly expanding sectors of the provincial economy: over 1,000 band and privately owned businesses are in existence.63 Gaming has become an important aspect of the Saskatchewan First Nations economy. The first casino was launched by the Whitebear First Nations in defiance of provincial wishes, and a First Nations Gaming Agreement was arrived at in 1995, leading to the creation of four First Nations-controlled casinos operated by the Saskatchewan Indian Gaming Authority. In 2002, a 25-year Gaming Framework Agreement was signed. Of $29.4 million in profits in 2003, 37.5% went to the provincial government, 37.5% to the First Nations Trust Fund, and 25% to community development corporations.64

Urbanization

Since the 1960s, there has been a general trend, encouraged originally by government assimilation policies, for First Nations individuals and families to move to urban centres in pursuit of education and job opportunities. Today, 47% of the First Nations population resides in urban centres; owing to problems of racism and lack of training, large areas of urban poverty have sprung up in Regina and Saskatoon. This phenomenon is accompanied by a high crime rate, the formation of gangs, and a high incarceration rate.65 Indian and Métis Friendship Centres (see Aboriginal Friendship Centres of Saskatchewan) started to come into existence in the 1960s to ease the transition of Indigenous Peoples into urban areas and began to receive federal funding under the Migrating Aboriginal Peoples program in 1972. Today, thirteen centres continue to offer social and program supports in Saskatchewan.

One of the innovations providing hope for the future is the creation of Urban Reserves66: there are now over twenty urban satellite reserves, in and around the major urban centres of Saskatoon, Regina, and Prince Albert. urban reserves provide a unique opportunity for First Nations to participate in the larger economy and greater employment opportunities for urban Indigenous residents.

Socio-Economic Conditions

As a group, the Indigenous population continues to be youthful, with a large though diminishing birthrate: 49.9% of the Indigenous population is below the age of 20, compared to 26.5% for the general provincial population. In terms of well-being, Indigenous people remain among the most impoverished, disadvantaged, and undereducated in society. The Indigenous labour force unemployment is 23%, five times that of 4.8% for the non-Indigenous population.67 Indigenous people continue to be severely underrepresented in professional occupations such as the medical and justice systems. In Saskatoon, 64% of the Indigenous population falls under the Low Income Cutoff Poverty Line, compared to 18% in the non-Indigenous population of the city. Housing is a reflection of this situation, along with crime and incarceration statistics. Mortality rates are high; adoptions and effective provision of social services are issues of concern. Disparities continue to exist in rural areas, where First Nations youth who lack employment opportunities and access to recreational facilities tend to become involved in crime. first nations women have also faced unique social challenges. Indian women had lost Indian Status under previous provisions of the Indian Act, but they and their children have been able to apply for reinstatement under Bill C-31 (1985). The association representing First Nations women is the Saskatchewan Indian Womens’ Association.

Law and Justice Issues

Indigenous hunting and fishing rights have been a long-standing source of dispute, as the implementation of federally protected treaty rights comes into conflict with provincial wildlife enforcement management; one compromise is to involve First Nations in their own enforcement, licensing and conservation initiatives.68 Water rights are another controversial area, with provincial water management often impinging on Indian lands. The justice system faces challenges when dealing with Indigenous people, as they constitute over 70% of inmates held in provincial correctional institutions. The investigation of the freezing deaths of Indigenous people outside of Saskatoon, such as the Commission of Inquiry into the death of Neil Stonechild,69 placed a focus on relations with the police. The Saskatchewan Justice Reform Commission, established in 2001 to carry out investigations, has made recommendations including the creation of an independent complaints investigation agency.70

One of the solutions being pursued is the development of Indigenous policing services, with emphasis on recruitment into mainstream agencies such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, as well as agreements to create reserve-based First Nations police forces. Courts are also beginning to provide greater clarity about Métis and Non-Status Indian legal issues, hunting and fishing, and restorative justice.

Contemporary Indigenous Arts

Traditional Indigenous art forms such as beading and hide work continue to thrive while contemporary Indigenous artists such as Allen Sapp and Gerald McMaster explore new avenues within which to interpret Indigenous experience (see Indigenous Artists, Contemporary and Indigenous Artists, Traditional). The Saskatchewan First Nations artistic community is the birthplace of internationally acclaimed singers like Tom Jackson, and of actors such as Gordon Tootoosis. There is a growing interest in Indigenous Theatre: for example, the Saskatchewan Native Theatre, founded by Indigenous cultural leaders in Saskatoon in 1999, has generated a great deal of interest and support from the community.

Indigenous Media began to emerge in the 1960s with the establishment of news magazines such as The Saskatchewan Indian and The New Breed. There now exist radio stations and television programs dedicated to Indigenous audiences. There is also a burgeoning community of Indigenous Writers, one of the best-known being Métis writer Maria Campbell.71

Indigenous cultural tourism is attracting increasing numbers of international visitors, who can witness any one of a number of regional powwows or experience cultural settings such as Wanuskewin Heritage Park, located on the outskirts of Saskatoon. Back to Batoche Days, held each July at the National Historic Site of Batoche, represent the central annual cultural and social gathering of the Métis.

The North

Over 80% of the approximately 40,000 inhabitants of northern Saskatchewan are Indigenous. While the peoples of the north face unique challenges because of geographical isolation and small populations, Indigenous peoples have the opportunity to become major players in areas such as resource management and environmental protection. The Prince Albert Grand Council’s investment in a variety of economic ventures including hotels and office buildings, as well as corporations such as Kitsaki Management Limited Partnership owned by the La Ronge

Towards a Shared Future

Observers sometimes refer to “two solitudes” when discussing Indigenous/non-Indigenous relations in the province. However, when considering the degree of segregation that existed prior to the 1960s under the federal policy of isolating Indians on reserves, the changes that have occurred since then are dramatic. With improved access to health care, First Nations have made great strides in terms of overcoming health challenges, and instead of being a “dying race” are now the most rapidly expanding portion of the provincial population. Currently, close to half of the children entering school age have Indigenous heritage, and it is anticipated that by the end of the 21st-century persons having some Indigenous ancestry will be a majority.

Indigenous peoples are in the process of successfully defending and securing their rights, an arrangement that brings hundreds of millions of federal dollars into the province. While unemployment rates remain high, educational participation has greatly increased, particularly at the post-secondary level. Other challenges, such as finding ways to vitalize rural First Nations reserve economies, will involve much imagination, commitment, and developmental support. Life has changed dramatically for Indigenous peoples in this province—beginning with the fur trade, then moving into the reserve period, and now largely in urban centres—but the story has been one of survival, adaptation, and versatility. One hopes for a future in which, as the treaty signatories originally envisioned, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous societies can co-exist while respecting each other’s cultures and rights. Despite the challenges facing them, Indigenous peoples in Saskatchewan are undergoing a social and cultural renaissance. Such a society can only become richer in heritage as well as more prosperous overall when Indigenous peoples regain control over their destinies and once again become a vital force in the lands that they rightly call their home.

Notes

1. The term for Cree varies according to dialect. Plains Cree

2. Olive Dickason, Canada’s First Nations (Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 1997), 11.

3. Henry Epp, Long Ago Today: The Story of Saskatchewan’s Earliest People (Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Archeological Society), 58.

4. Blair Stonechild, Neal McLeod and Rob Nestor, Survival of A People (Regina: First Nations University of Canada, 2004), 2. Health and Welfare Canada, “Cultural Calendar–1986” contains detailed diagrams of the Circle of Life.

5. Katherine Pettipas, Severing the Ties that Bind (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1994), 185.

6. John Milloy, The Plains Cree: Trade, Diplomacy and War 1790 to 1870 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1988), 6–7.

7. Arthur Ray, Indians in the Fur Trade (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974), 4.

8. Milloy, The Plains Cree, 8–10.

9. David Mandelbaum, The Plains Cree (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1979), 26.

10. Ibid., 32.

11. Milloy, The Plains Cree, 31 and 43–45.

12. Ibid., 50.

13. Patricia Albers, “Plains Ojibway,” in Handbook of North American Indians (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 2001), 659; and Laura Peers, The Ojibway of Western Canada (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1994), 46.

14. Albers, “Plains Ojibway,” 652; and Treaty Number Four Council of Chiefs, “Treaty Four First Nations Governance Model” (October 23, 2000), 2.

15. Milloy, The Plains Cree, 51.

16. Peter Newman, Caesars of the Wilderness (Markham,

17. Dickason, Canada’s First Nations, 242.

18. Ray, Indians in the Fur Trade, 182–192.

19. Ibid., 203–212.

20. Deanna Christensen, Ahtakakoop (Shell Lake, SK: Ahtakakoop Publishing, 2000), 169.

21. Neal McLeod, “Plains Cree Identity,” Canadian Journal of Native Studies 20, no. 2 (2000): 441.

22. Alexander Morris, The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North West Territories (Toronto: Coles [reprint], 1971), 43.

23. D.N. Sprague, Canada and the Métis 1869–1885 (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1988), 94.

24. Indian Claims Commission, Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation Inquiry Report, 14 ICCP (Ottawa: 2001), 26.

25. Morris, The Treaties of Canada, 126.

26. Ibid., 178.

27. Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 98–99.

28. Blair Stonechild, “The Iron Alliance and Domination of the Northern Plains, 1690–1885: Implications for the Concept of Iskunikan” (unpublished, 2002), 15.

29. Hugh Dempsey, Big Bear: The End of Freedom (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1984), 126.

30. Blair Stonechild and Bill Waiser, Loyal Till Death (Calgary: Fifth House, 1997), 50–60.

31. Dempsey, Big Bear, 123.

32. Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal Till Death, 4.

33. Ibid., 151.

34. Frank Anderson, Almighty Voice (Aldergrove, BC: n.p., 1971).

35. J.R. Miller, Shinguak’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1996), 153; and John Milloy, A National Crime; The Canadian Government and the residential school System 1879 to 1896 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1999), 40.

36. House of Commons, Debates, 46 Vict. (May 9, 1883) 14: 1107–1108.

37. Miller, Shinguak’s Vision, 103.

38. Ibid., xiv.

39. Stewart Raby, “Indian Land Surrenders in Southern Saskatchewan,” Canadian Geographer 17, no. 1 (Spring 1973.)

40. Norma Sluman and Jean Goodwill, John Tootoosis (Ottawa: Golden Dog, 1982), 134.

41. Fred Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers (Penticton: Theytus Books, 1985), contains detailed accounts of individual Aboriginal veterans and their experiences.

42. Harry Hawthorne, A Survey of Contemporary Indians of Canada: Economic, Political Educational Needs and Policies, 2 vols. (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1966).

43. Laurie Barron, Walking in Indian Mocassins (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997), 76–77.

44. Ibid., 134.

45. Canada Act (1982), Section 35, 1982.

46. Peggy Brizinski, Knots in a String (Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan, 1993), 10.

47. Federation of Saskatchewan Indians, Saskatchewan and the Aboriginal Peoples in the 21st Century (Regina: Printwest, 1997).

48. First Nations and Northern Statistics, Registered Indian Population by Sex and Residence 2003 (Ottawa: Indian and Northern Affairs Ottawa, 2003), xviii.

49. Sally Weaver, Making Indian Policy: The Hidden Agenda 1968–70 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981), 171.

50. Rick Ponting and Roger Gibbins, Out of Irrelevance (Toronto: Butterworths, 1980), 198.

51. Meadow Lake Tribal Council, Tripartite Agreement in Principle, January 22, 2001.

52. Office of the Treaty Commissioner, Treaties as a Bridge to the Future (Saskatoon: Office of the Treaty Commissioner, 1998), 36.

53. Brizinski, Knots in a String, 11.

54. James Pitsula, “The Saskatchewan CCF Government and Treaty Indians,” Canadian Historical Review 74, no. 1 (1994).

55. Federation of Saskatchewan Indians, Indian Education in Saskatchewan, Vol. 2 (Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Indian Cultural College, 1973), 149.

56. Barron, Walking in Indian Mocassins, 36.

57. Saskatchewan Education, Reaching Out: The Report of the Indian and Métis Education Consultations, Regina, 1985.

58. Maureen Lux, Medicine that Walks: Disease. Medicine and Canadian Plains Native People 1880–1940 (Toronto: University of Toronto, 2001), 213.

59. Thomas Isaac, Aboriginal Law (Saskatoon: Purich Publishing, 1995), 271.

60. Peggy Martin-McGuire, First Nations Surrenders on the Prairies 1896–1911 (Ottawa: Indian Claims Commission, 1998), 27.

61. www.fnmr.gov.sk.ca/html/documents/tle/TLEFA_Schedule1.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2005.

62. Robert Anderson, Economic Development among the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada (Toronto: Captus, 1999), 161.

63. Ibid., 174.

64. Saskatchewan Indian Gaming Authority, Annual Report 2002–2003, 3.

65. Commission on First Nations and Métis Peoples Justice Reform, Legacy of Hope: An Agenda for Change (Regina: n.p., 2004).

66. Laurie Barron and Joseph Garcea, Urban Indian Reserves: Forging New Relationships in Saskatchewan (Saskatoon: Purich Publishing, 1999).

67. Saskatchewan Government Relations and Aboriginal Affairs, “Demographic Data–Aboriginal Population in Saskatchewan” (2001).

68. Isaac, Aboriginal Law, 234.

69. Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Matters Pertaining to the Death of Neil Stonechild (Regina: Queen’s Printer, 2004).

70. Commission on First Nations and Métis Peoples Justice Reform.

71. Campbell is

Blair Stonechild

Further Reading

Barron, L. 1997. Walking in Indian Moccasins. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Barron, L. and J. Garcea. 1999. Urban Indian Reserves: Forging New Relationships in Saskatchewan. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing.

Campbell, M. 1973. Halfbreed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Cardinal, H. and W. Hildebrant. 2000. Treaty Elders of Saskatchewan. Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

Beal, B. and R. McLeod. 1984. Prairie Fire: The North West Rebellion. Edmonton: Hurtig.

Carter, S. 1990. Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Christiansen, D. 2000. Ahtakakoop and His People. Shell Lake, SK: Ahtakakoop Publishing.

Dempsey, H. 1984. Big Bear: The End of Freedom. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

Dickason, O. 1997. Canada’s First Nations. Don Mills,

Elias, D. 1988. The Dakota of the Canadian North West. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Grant, J. 1984. Moon of Wintertime: Missionaries and the Indians of Canada in Encounter. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lux, M. 2001. Medicine That Walks: Disease. Medicine and Canadian Plains Native People 1880–1940. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Mandelbaum, D. 1979. The Plains Cree: An Ethnographic, Historical and Comparative Study. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center.

Milloy, J. 1988. The Plains Cree: Trade, Diplomacy and War, 1790 to 1870. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

——.1999. A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Miller, J. 1996. Shinguak’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Newman, P. 1987. Caesars of the Wilderness. Markham,

Peers, L. 1994. The Ojibway of Western Canada. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Pettipas, K. 1994. Severing the Ties That Bind. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Ray, A. 1974. Indians in the Fur Trade. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Ray, A., J. Miller and F. J. Tough. 2000. Bounty and Benevolence: A History of Saskatchewan Treaties. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sluman, N. and J. Goodwill. 1982. John Tootoosis. Ottawa: Golden Dog.

Sprague, D.N. 1988. Canada and the Métis, 1869–1885. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Stonechild, B. and B. Waiser. 1997. Loyal Till Death: Indians in the North West Rebellion. Calgary: Fifth House.