Introduction

Assessment drives learning1. How we assess learners is a major force in ensuring that learners are prepared for the next stage of training by driving the studying they do and by providing feedback on their learning. This Cell is designed to give you an overview of the major types of assessments along with their strengths and weaknesses so you can help make better decisions about how to assess your learners. You will also end up remembering and understanding the ABCs of assessment: assess at an appropriate level, be wary of weaknesses, and consider complementarity.

Learning Objectives (what you can reasonably expect to learn in the next 15 minutes):

- List and classify different assessment methods according to Miller’s pyramid of clinical competence.

- Given a testing situation (or goal) select and justify an assessment method.

- Explain the ABCs of assessment and apply to testing situations.

To what extent are you now able to meet the objectives above? Please record your self-assessment. (0 is Not at all and 5 is Completely)

To get started, please take a few moments to list the assessment methods that you are familiar with. Can you think of a weakness or two? Write them out here so you can refer back to them shortly:

Now proceed to the rest of this CORAL Cell.

An Overview of Common Assessment Methods based on Millar’s Pyramid

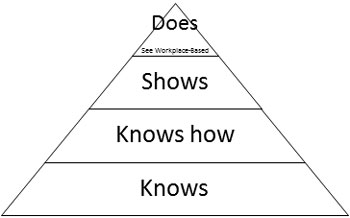

A simple way to classify assessment methods is to use Miller’s pyramid (1):

The bottom or first two levels of this pyramid represent knowledge. The “Knows” level refers to facts, concepts and principles that learners can recall and describe. In Bloom’s taxonomy this would be remembering and understanding. The “Knows how” level refers to learners’ ability to apply these facts, concepts, and principles to analyse and solve problems. Again, in Bloom’s taxonomy, this would match applying, analyzing, evaluating, and creating of the cognitive domain. The “Shows” level refers to requiring students to demonstrate performance in a simulated setting. Finally, the “Does” level refers to what learners do in the real world, typically in the clinical setting for medical education. The “Does” level is addressed in more detail in the companion Cell, Methods of Workplace-based Assessment.

Clearly, the higher the level on the pyramid, the more authentic and complex the task is likely to be. The less standardised too. And typically as you move up the pyramid, it takes more time per case or question to assess attainment of the objective. This is a practical issue because clinical competence varies across cases, a phenomenon called case-specificity2. Good multiple-choice questions may be less authentic than real patient interactions, but you can test a broader range of cases in a given amount of time with well-written MCQs compared to the traditional long case oral exam or even the OSCE. Every testing method has strengths and weaknesses so it is usually a good idea to use a variety of methods to achieve complementarity (ABCs!). The accompanying table briefly describes and explains a variety of testing methods.

“Knows” and “Knows how”

To test knowledge, you can use written or oral questions. These can be selected-response, where learners have to pick one or several answers from a pre-specified list (multiple-choice questions or pick N questions – where students must pick a given ‘N’ number of options would fall in this category), or constructed-response where students must generate their answer from scratch (short-answer questions for example). Table 1 contains a more complete presentation of various testing approaches. Whether a question tests at the first or second level of the pyramid is not determined by its format but rather by the task implied by the question. Compare the two questions below: which one tests at a higher level?

Selected-response: single-best answer multiple choice question

You are called to examine Mrs. Peters, a 65 year-old woman, with a history of diabetes and hypertension. Her current illness started with a sore throat but got steadily worse. She has been in bed for 3 days with a temperature of 39 C and a dry cough. On examination, her temperature is 39.5, HR 90 bpm, BP 120/80, RR 18/min. Her pharynx is red but the rest of the examination including chest auscultation, is normal. Which of the following is the most likely pathogen?

- Influenza

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Rhinovirus

- Streptococcus A

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

Constructed-response: short answer question

What are the three most common symptoms of influenza?

The MCQ tests at a higher level. Analysis and application of knowledge is required to select the best response but the short answer question is just asking for recall of knowledge.

To test knowledge application (“Knows how”), regardless of question format, the task must involve some sort of problem or case. Case-based multiple-choice questions are often more difficult to write so many of us have been exposed to the easier factual recall multiple-choice questions, which has created an erroneous perception that MCQ only test trivia. However MCQs can in fact be used to test clinical reasoning and have the advantage of enabling assessment of a broad range of cases in a short time. Of course, a written examination will never fully capture the complexities of actual clinical work, with challenges such as history-taking in patients who may be upset or have hearing issues, in a clinical setting characterised by noise and multiple interruptions. In other words, written examinations overestimate competence in clinical reasoning.

“Shows”

The Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) is a typical method used here. The OSCE enables a fairly standardized assessment of clinical competence. By breaking down clinical work into tasks that can be performed in 5-15 minutes, OSCEs can test several cases (typically 10-15). However this tends to reduce clinical competence to discrete skills and fails to capture the integration of skills required in actual clinical practice. Simulated Office Orals - where the examiner both plays the patient and asks probing questions - is another method designed to assess the “Shows” level. See Table 1 for a more complete listing and description of various approaches to testing.

“Does”

Assessment in the clinical setting can focus on a single event (e.g. a single patient interaction) or be based on multiple observations aggregated across time. There are many tools - with as many acronyms - to assess single events: e.g., the mini-CEX (mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise), PMEX (Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise), O-SCORE (Ottawa Surgical Competence Operating Room Evaluation). Tools that aggregate across multiple observations include end of clinic forms (e.g. field notes) or end-of-rotation forms (often referred to as ITERs, In-Training Evaluation Reports or ITARs – In-Training Assessment Reports). What can be observed can also vary, from patient encounters to procedures, case presentations, interactions with nurses and other healthcare professionals, notes, letters, and others. Please consider completing the sister Cell in the CORAL Collection specifically on the topic of workplace-based assessment.

Choosing an assessment method

In choosing an assessment method, multiple factors come into play, including feasibility. However, the goal will be to maximise validity within the constraints of your setting. Validity does not reside in the method alone; a test is not in and of itself valid or not valid. The same method can be implemented well or poorly, appropriately or not, and this will determine whether scores are being used appropriately (in a valid manner). Many factors influence whether or not the same tool is used in a valid way or not. An IQ test might help predict academic success but not marital or relationship success. The same multiple-choice exam in an invigilated versus non-invigilated setting, where students may collaborate or check answers in textbooks, may not be valid to use for summative decisions about individuals’ clinical knowledge.

The ABCs

In summary, there is no silver bullet for assessment in the health professions. Different methods have their purposes, strengths and weaknesses (see again Table 1; a similar table for the “Does” level is available in the Workplace-based Assessment Cell). In making decisions about which method (and ideally methods) to use, you should (here again are the ABCs but with more detail):

Assess at the Appropriate level of Miller’s pyramid (and Bloom’s taxonomy)

Beware of the weaknesses of each method and the factors that will influence validity in your own setting

Consider the Complementarity of different methods in the overall program of assessment to leverage the strengths of different methods and compensate for their individual weaknesses

Table 1: Methods of assessment Levels 1-3 of Miller’s pyramid

|

Method |

Use to assess |

Strengths |

Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

Knows |

|||

|

1. Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) Stem followed by multiple possible answers |

|

|

|

|

2. Essay, short answer questions Written response to a question or assigned task. Short answer questions involve responses of one or two paragraphs or less

|

|

|

|

Shows |

|||

|

3. Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) Multiple separate task stations with performance requirements. |

|

|

|

|

4. Simulated Office Oral (SOO) Examiner simulates a patient problem which the learner must manage |

|

|

|

Adapted from faculty development materials, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University

Check for Understanding

Self-assessment

Please complete the following very short self-assessment on the objectives of this CORAL cell.

To what extent are you NOW able to meet the following objectives? (0 is not at all and 5 is completely)

To what extent WERE you able the day before beginning this CORAL Cell to meet the following objectives? (0 is not at all and 5 is completely)

Thank you for completing this CORAL Cell.

We are interested in improving this and other cells and would like to use your answers (anonymously of course) along with the following descriptive questions as part of our evaluation data.

Thanks again, and come back soon!

The CORAL Cell Team

References:

1. Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine. 1990;65(9).

2. Norman G, Bordage G, Page G, Keane D. How specific is case specificity?. Medical education. 2006 Jul 1;40(7):618-23.

Further reading:

Epstein R. Assessment in Medical Education. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:387-96

Wass V, Van der Vleuten C, Shatzer J, Jones R. Assessment of clinical competence. The Lancet. 2001;357(9260):945-9.

van der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Scheele F, Driessen EW, Hodges B. The assessment of professional competence: building blocks for theory development. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2010;24(6):703-19.

Norcini J, Anderson B, Bollela V, Burch V, Costa MJú, Duvivier R, et al. Criteria for good assessment: Consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Medical Teacher. 2011;33(3):206-14.

Credits:

Author: Valérie Dory, McGill University

Reviewer/consultant:

Series Editor: Marcel D’Eon, University of Saskatchewan