Indigenizing Academia

by Stryker Calvez

The Indigenous Peoples of Canada have a long and complicated history with Canadian society; this includes a problematic relationship with researchers, academics, and other data and information collectors (RCAP, 1999). Over the last 20 years, academia has been coming to terms with the necessity to develop new and alternative approaches to support Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people to build a society based on decolonization, indigenization and reconciliation practices. For many educators the changes needed in their classroom are not much different than the changes promoted by the teaching and learning literature (e.g., student-centered teaching, experiential learning, critical reflection, consensus building, active listening, etc.). Similarly, learning that takes place through research is based on the best practices that are outlined in the Tri-council Policy Statement based on Respect for Persons, Concern for Welfare, and Justice (TCPS2, 2010). Together, these two sources provide a strong set of guidelines that can and will support the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge, history and worldviews in postsecondary institutions. But, they are not enough.

An important challenge for Western academia is that it is founded and dominated, to some degree, by positivist/postpositivist beliefs about knowledge that contrast the relativistic approach to knowledge that Indigenous people have taken (Little Bear, 2000). Western institutions have been formed around this approach to knowledge with all of their policies and procedures developed to promote and value a specific set of ways for understanding and knowing the world. Due to the rigorous enculturation process of postsecondary educations systems, many academics are challenged to appreciate and value how Indigenous Peoples conceptualize, understand and know the world. Very few non-Indigenous academics understand the spirituality of our knowledge and the important links to land and sky, the four directions, and all our relations (i.e., ancestors, animals, and plants). Indigenous knowledge is interconnected and relational to time, place, season, community, person and more. So it is not surprising that Indigenous approaches to knowledge can appear to be antithetical to Western approaches to knowledge. This not to say that Western academics are not good at describing Indigenous worldviews, but they do often lack the ability to communicate the meaning, role, and use of these worldviews effectively and appropriately (Little Bear, 2000). This is why postsecondary institutions need to take the time to develop cautious and informed practices that prevent the unintentional codification of Indigenous knowledge, history and worldviews to be more comfortably compatible with Western values and understandings. To not do this is to contribute to the propagation of inaccurate understanding and support of Indigenous Peoples - colonization.

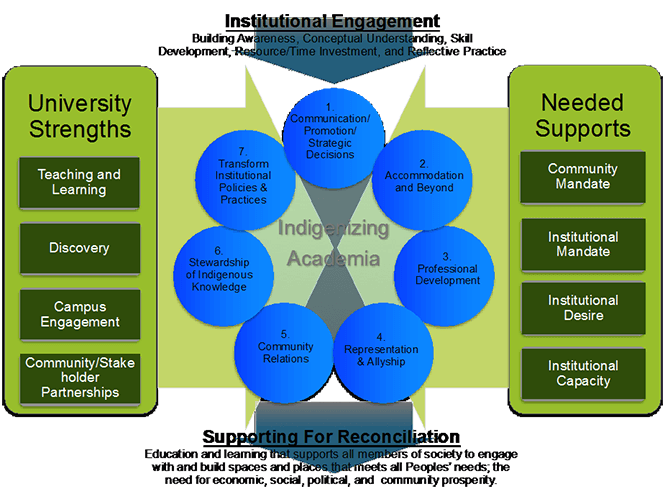

The process of offering genuine and meaningful support to Indigenous people and to open the way to benefiting from these relationships is straightforward but will take time and critical reflection. In order to ensure that postsecondary institutions do not cause further harm to Indigenous Peoples is through decolonization and indigenization. Decolonization can be understood as dismantling of barriers, intentional or otherwise, that prevent Indigenous people and their ideas from prospering in Canadian society independently. Indigenization is the integration of Indigenous people and their ideas into institutions and society in a manner that supports their visions and aspirations for self-determination, well-being, growth and prosperity. It is through prioritizing and undertaking these two processes that a postsecondary institution can begin to participate in reconciliation and supporting the Calls to Action.

Foundational Principles for Indigenization

Colonization was an active approach to globalization, where one culture actively imposed its will on another. Today, that continues but in more insidious ways that is often invisible to those with power and privilege. An active and intentional process is needed to negate colonialism or postsecondary institutions will become complicit in contributing to the limits and restrictions placed on Indigenous Peoples for a quality, independent, and self-determined life. The process forward is through decolonizing and indigenizing the University of Saskatchewan in a strategic, intentional, and substantive manner.

Decolonization is a process of critical reflection, consideration, consultation, and revisioning of Western approaches, policies, and practices to teaching and learning. Discovering and dismantling barriers to learning for everyone, non-Indigenous and Indigenous, is the goal.

Indigenization is a processes advocacy for, education about and relationship building with the Indigenous Peoples of Canada. This is directed at everyone; non-Indigenous and Indigenous faculty, staff, students, stakeholders, and communities. The goal is reciprocal and mutual respect.

A commitment to the transformative process of decolonizing and indigenizing the University of Saskatchewan will necessitate a dedicated response that is equal to or greater than the level of concern, fear, and complacency that exists toward institutional change and the appropriate inclusion of Indigenous People at the University. A successful commitment will need to be built into and reinforced throughout all University, college and academic units’ processes, policies, and practices.

A Model for Decolonizing and Indigenizing Academia

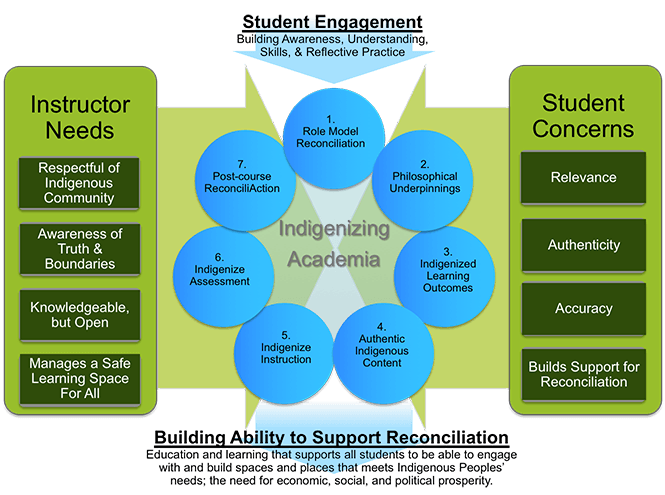

A Model for Decolonizing and Indigenizing Courses

For information, contact the Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching and Learning.