Crediting Indigenous Knowledge and Sources

What are the elements we must include when citing and crediting Indigenous Knowledge and sources?

By Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching and LearningThis article is the seventh in a series on integrating EDI principles into our teaching and learning design and practices. It is a collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff members.

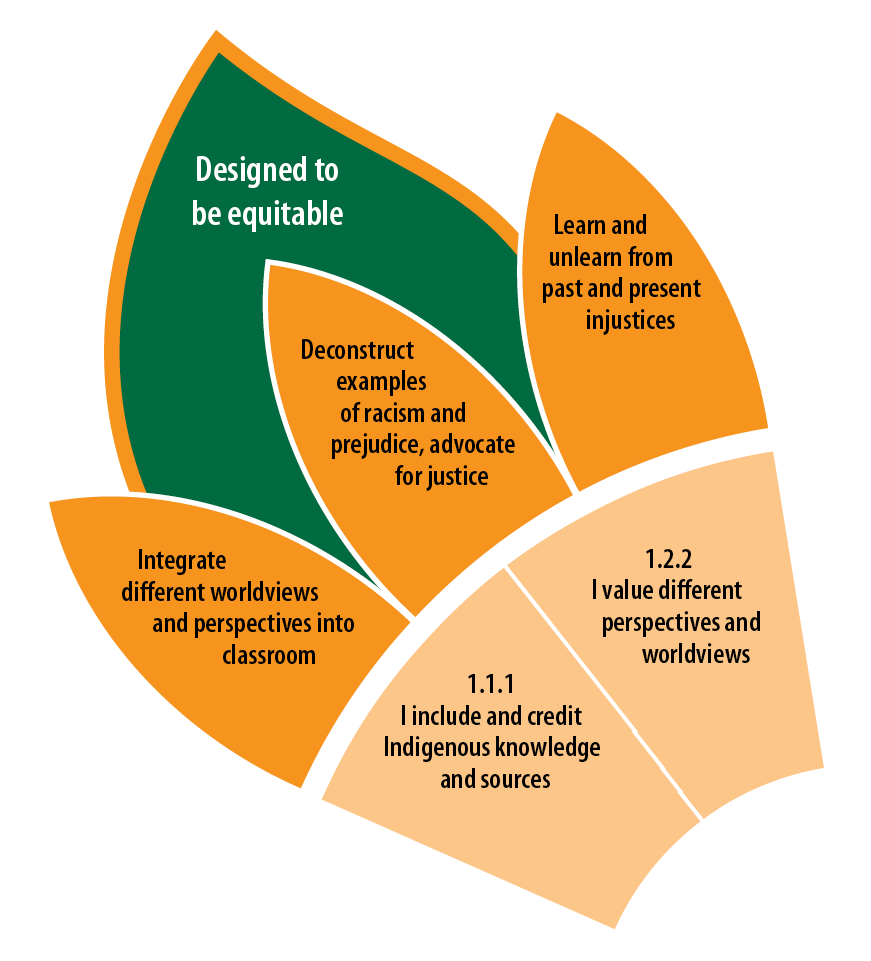

‘I include and credit Indigenous knowledge and sources’ is one of the Designed to be Equitable indicators from USask’s EDI Flower and the Certificate for University Teaching (CUTL).

|

Embracing the Designed to be Equitable principle means we actively include and cite Indigenous worldviews, emphasizing the importance of valuing diverse perspectives and worldviews. |

Crediting Indigenous knowledge and sources is one important way to show we respect, value, and recognize Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge. We model our attitudes toward these knowledges when they are included in our syllabi, curriculum, classrooms, as well as cited in our writing and research.

Additionally, the ways we cite Indigenous oral traditions and teachings, challenges the colonial biases inherent in traditional citation methods.

Here, we explore guidelines and practices for citing Indigenous knowledges, drawing on Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples by Gregory Younging (Opaskwayak Cree Nation) and the work of Lorisia MacLeod (James Smith Cree Nation) with NorQuest College.

The importance of proper citation

Gregory Younging's Elements of Indigenous Style emphasizes the need for respectful and accurate representation of Indigenous Peoples in writing. Younging advocated for the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and the proper attribution of Indigenous knowledge to combat the erasure and misrepresentation of knowledge, people, and communities.

Given the diversity of nations, we need to recognize the specific nation or community from which the knowledge originates. When we cite our sources, we are:

- acknowledging contributions others have had on our learning,

- providing readers with opportunities for deeper exploration,

- adding credibility to our ideas (when using authentic sources),

- avoiding breaking of protocols, and

- situating our work with the discipline (Indigenous Information Literacy, KPU, 2022)

Cite published materials as for all other writing, using your discipline’s formatting guidelines.

Citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers

Lorisia MacLeod, in her article More Than Personal Communication, addressed the limitations of traditional citation styles like APA and MLA when it comes to Indigenous Oral Knowledge. MacLeod developed citation templates in collaboration with NorQuest College to provide a more respectful and accurate way to cite Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers, than simply using a ‘personal communication’ format. These templates include elements such as the Elder's name, their nation or community, the treaty territory (if applicable), and a brief description of the teaching. MacLeod also provides templates for reference list formatting.

An APA citation would look like this:

Last name, First name., Nation/Community. Treaty Territory if applicable. City/Community they live in if applicable. Topic/subject of communication if applicable. Date Month Year.

For example:

Cardinal, Delores., Goodfish Lake Cree Nation. Treaty 6. Lives in Edmonton. Oral teaching. 4 April 2004.

Practical steps for implementation

- Consult Indigenous style guides: Use resources like Younging’s (2018) Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples to guide respectful inclusion of Indigenous perspectives, available online through the USask Library.

- Use appropriate templates: Adopt citation templates developed by Indigenous scholars, such as those by Lorisia MacLeod, to ensure proper attribution. See NorQuest College Library.

- Engage with Indigenous communities: Build relationships with Indigenous communities and seek their guidance on how to represent their knowledge accurately.

- Reflect on citation choices: Regularly review and reflect on citation practices to ensure they are inclusive and respectful.

Conclusion

As we examine our citation practices and question who is cited and why, we are making a conscious effort to include voices of Indigenous scholars, Elders and Knowledge Keepers. Formal citation also reflects how we value and respect the knowledge. Who and how we cite matters.

| “The act of citation is a consistently developing area especially as more voices join the ongoing conversation about how to share knowledge and generate research in a good way. These conversations are vital for matters such as land title and treaty, health, cultural safety, national security, the environment, economic development, climate change, and more.” - Indigenous Oral Sources, Citation Templates, University of Calgary |

- Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guidebook for Writing by and About Indigenous Peoples, Gregory Younging (Opaskwayak Cree Nation), available online through USask Libraries

- Indigenous Information Literacy, 2022, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, Pressbooks.

- Indigenous Knowledges and Canadian Copyright Law, USask University Library.

- KPU – Citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers. Includes videos on citing in APA, Chicago and MLA

- More Than Personal Communication: Templates for Citing Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers, Lorisia MacLeod (James Smith Cree Nation)

- Indigenous Information Literacy: Citation Guide, NorQuest College Library

- The Publication Manual of the APA (7th ed.), instructs that ‘non-recoverable’ sources such as conversations with Elders or Knowledge Keepers be cited only in-text and not be given a reference list entry.

-----

This article series is a detailed exploration of the USask EDI Framework Principles and its application in course design and our classrooms.

- Empowering Education: Embracing Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion at USask

- Fostering Inclusive Learning Environments at USask: The EDI Framework for Action

- A Teaching Tool: The EDI Flower

- Positionality in the Classroom: An EDI Principle

- Designed to be Equitable: An EDI Principle

- Honouring Indigenous Knowledges in Higher Education

- Crediting Indigenous Knowledge and Sources (current article above)

Title image is from the Public Domain.