Adding Experiential Learning to an Introductory Course

Boost engagement and learning by integrating experiential activities into introductory courses. Learn how practical experiences enhance academic understanding.

By Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching and LearningIt can feel overwhelming to add experiential learning to large classes, particularly at the first and second year level of undergraduate learning. For Dr. Bob Patrick from the Department of Geography and Planning, the new USask experiential learning cycle helped him revamp a 200-level course project into an authentic learning experience with opportunities for reflection and feedback.

Dr. Patrick’s course is about measuring sustainable development in cities. With a class size of 60 students, he decided to make this learning adventure more engaging by making experiential learning explicit and bringing the world into his classroom. Here’s how he did it:

Empowering Students with Choice and Voice

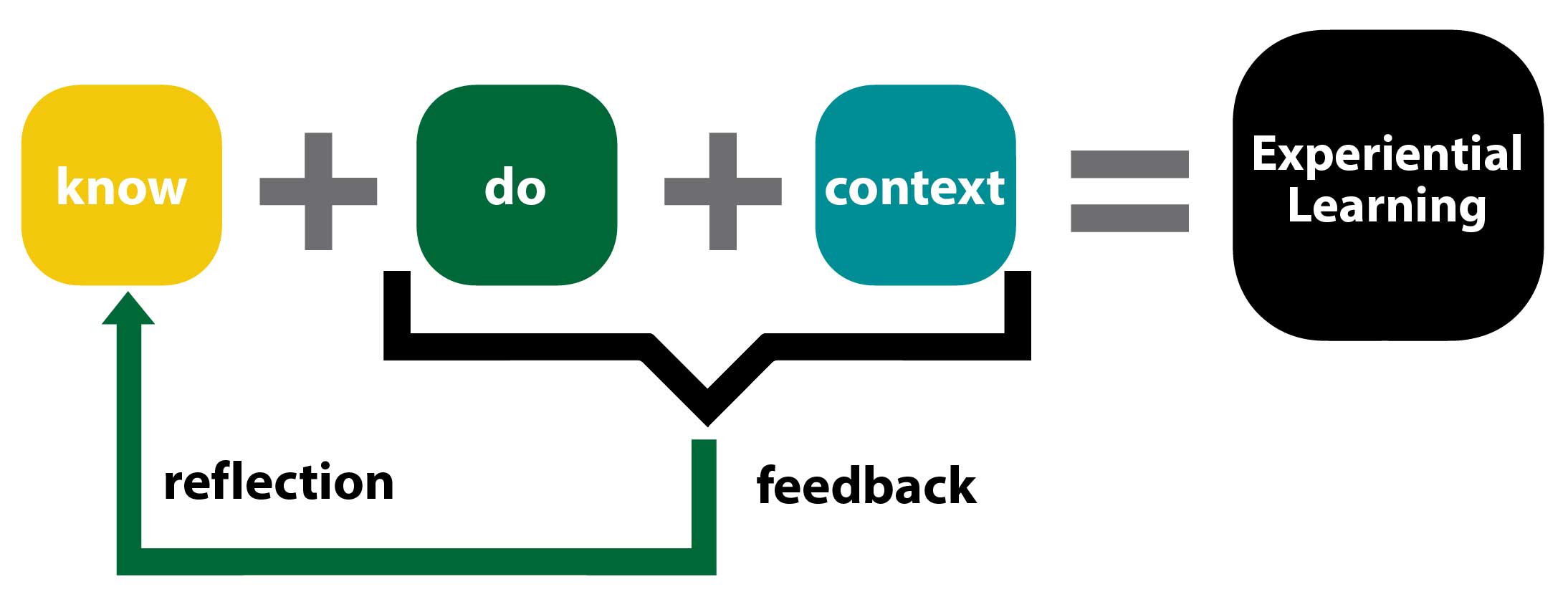

Instead of handing out predefined projects, Dr. Patrick empowered students to propose their own projects. This change gave students a sense of ownership over their work, making the learning process more authentic. He also included the USask experiential learning cycle on the project plan so that students could explicitly see what they were asked to know, do, in context, with feedback and reflection. He did provide a list of examples to help guide their thinking, but this was a scaffold or support, not a mandate.

Customizable, yet Structured, Project Proposals

To further support students, Dr. Patrick introduced a template form and checklist and encouraged students to work in pairs. They drafted their proposals, but when Dr. Patrick went to evaluate them, he realized this was an opportunity to provide valuable feedback to students. Some students struggled with defining specific topics, so he had to adjust as well. The first round of proposals became a draft—a chance to make improvements and get things right. This was a crucial learning moment for both the students and the instructor.

A Learning Loop of Revision

Students then had the opportunity to revise and refine their proposals based on the feedback received. This iterative process not only improved their projects but also taught them the art of adapting and refining ideas. This wasn’t a ‘gotcha’ moment to take marks from students, but rather an opportunity for Dr. Patrick to show that instructor feedback and student reflection help improve learning. Most of the resubmitted proposals were clear and met the acceptable standard.

As he moved forward, Dr. Patrick found it essential to create more connections between lecture content and students’ projects. He reminded his class of the vital connections between theoretical knowledge and potential real-world project issues such as bus routes, wetland loss, and public seating. Determining if a project had measurable data and alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were key focus areas.

Continuous Feedback and Support

As mentioned, Dr. Patrick uses templates to give structure to progress reports. To avoid overwhelming students, he released forms one at a time, as needed, to ensure that everyone is literally on the same page. This also makes assessment easier as there is a predictable flow to each submission. A template for the progress report allowed students to share their challenges, ideas to overcome them, and lessons learned along the way in a structured way while still providing their unique answers. This step in experiential learning (the during phase) allows students to step back and assess where they are and where they want to go with the project.

Final Group Presentations

The culmination of the course involved final presentations. Each group had a 5-10 minute window to present their research question, methodology, and research findings. This helped students learn not only from their own experiences but also from the diverse approaches taken by their peers.

In the end, Dr. Patrick’s students were tasked with producing a final report of 2500 words, bringing their entire journey full circle. This transformative process took them from vague to well-structured projects, enhancing their skills in critical thinking, problem-solving, and real-world application. Watch this video to learn more about students’ experiences with this project format.

So, what can other educators learn from Dr. Patrick’s journey?

- Choice and Ownership: Giving students a say in their learning encourages engagement and fosters a sense of ownership over their education.

- Continuous Feedback: Regular feedback loops, check-ins, and opportunities to revise are vital for student growth and success.

- Real-World Connections: Linking classroom content to real-world issues makes learning more meaningful and actionable.

- Iterative Learning: The process of draft, refine, and revise is a powerful tool for improvement and growth.

Dr. Patrick’s experience is a testament to the power of authentic learning experiences and the positive impact they can have on both students and instructors. It’s a journey worth taking in any educational setting, and we hope it inspires you to consider how you can make your courses more engaging, meaningful, and impactful.

Connect with Dr. Bob Patrick to learn more.

Image credit: fauxels from Pexels