Progressing Your Program’s AI Strategy

We have been in a reactive phase of responding to AI where our focus has been on which uses of AI to permit in assessments. Now, two other areas need attention so we can shift into being proactive.

By Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching and LearningUSask Academic Leadership Series

November 2024 marks two years since OpenAI released ChatGPT to the public. Since then, many more AI models and tools have been released leading to significant changes both inside and outside of academia. Over this time, many leaders in higher education have been supporting faculty to think through the disruptive innovation of Generative AI. Because AI impacted our assessment practices first, we had to consider questions like:

- What does AI do or produce that relates to how we assess in our discipline?

- What uses or AI are or should be permitted during assessments?

- Are there ways to detect unpermitted uses of AI?

Leaders have helped faculty articulate expectations of AI use in common ways that students can understand and directed everyone to USask’s provisional principles and guidelines for students and educators. It was a substantial amount of unanticipated effort, as is the resulting effort to secure assessments and respond to academic misconduct.

However, by considering which uses of AI to permit in the assessments we are currently in the most reactive stage of responding to AI within teaching and learning in higher education. The more complex work is related to these two other key areas:

- What uses of AI will be required to prepare our students for their careers? What implications does this have for curriculum, instruction and assessment, and how we design our programs so we prepare our students?

- What ways of using AI for teaching and learning will we implement? Which ways will we reject and how will we make that decision locally and institutionally?

1. Requiring AI Use by Students

What this could look like:

- A program requires a student to interact with a simulated client or patient, as a performance task in early years to practice reasoning or communication skills.

- A program requires students to find errors in AI generated content to demonstrate literacy.

- A program requires students to analyze data using a combination of AI tools, such as transcription or visualization software.

- A program requires students to create simplistic chat agents to apply an understanding of disciplinary thinking.

- A program requires students to adjust additional drafts of work based on AI generated feedback about mechanics, tone, or structure of a written work.

- A program requires the production of creative work that includes both human and machine generated content to showcase creative skills and comment on the human condition.

What is the role for the leader?

As leaders, we need to have sufficient understanding of the opportunities presented by AI to be able to suggest, align with what professionals are using AI to do, and articulate why two seemingly similar uses might be highly desirable or highly problematic. We need to find faculty to lead curriculum work, navigate our internal processes, and respond well to concerns. Because we can be caught in-between students and faculty, we need clear criteria for the decisions we make, and the decisions need to be consistent with the long-term goals of the department or college, some of which may contradict other goals. Questions of how to position and future proof our programs often are set aside for more pressing problems; however, AI and academics will quickly become the problem if we don’t think proactively.

2. Using AI to Support the Effort of Teaching

What this could look like:

- An educator uses an AI tool to create a series of slides based on a document containing notes, or even, their talking on a subject.

- AI generates a course outline based on a set of criteria, and the educator revises it.

- An educator uses an AI tool to grade and/or provide feedback on student essays.

- The AI generates practices problems, analogies, sample data, or cases to be used during class, which saves a lot of time making instructional materials.

- The AI turns low level recall questions into higher level analysis or evaluation questions to make an exam more AI resistant.

- The faculty member uploads student work into an AI tool, and the tool says the student likely copied it from AI or had AI create it. (To date, USask has observed and communicated that such tools are not reliable).

What is the role for the leader?

As leaders, we are actively looking for tools that can save faculty time, as few faculty think we are sufficiently supportive of the time and effort of teaching. However, we need to help faculty think carefully about choosing the best time savers and avoiding the most problematic practices. We need specific procedures or common agreements about what is acceptable. Some uses of AI, like making the rough draft of a syllabus, are widely permitted across higher education globally, even without acknowledgment of AI use. Other uses, like grading student essays using AI, are widely prohibited, because students do not have alternative options, and the grading decisions are not being made using human judgement. Many of the other uses on the list above are widely acceptable in other universities if the AI use is acknowledged. Others uses are polarizing or undecided, leaving the leader making complex judgement calls in a quickly evolving and controversial area.

While on the topic of AI and saving faculty and leader time, responding to academic misconduct cases takes significant time, cognitive effort, and emotional labour. As leaders, we should be working with faculty to proactively establish clear expectations for how students can use and acknowledge AI in assessments. By communicating these clear expectations, we can avoid misconduct, and, in cases where it does occur, respond quickly and consistently.

Conclusion

As leaders, we are in progress on helping faculty and students know where to go to develop basic AI literacy skills and how to understand what uses are permitted in assessment and why. The next horizons are 1) what our programs will require students to do with AI, and 2) what teaching tasks can be appropriately devolved to AI. A lot of additional learning and leadership of collegial work is ahead of us. When ready, we encourage you to connect with the Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching and Learning to help advance this work.

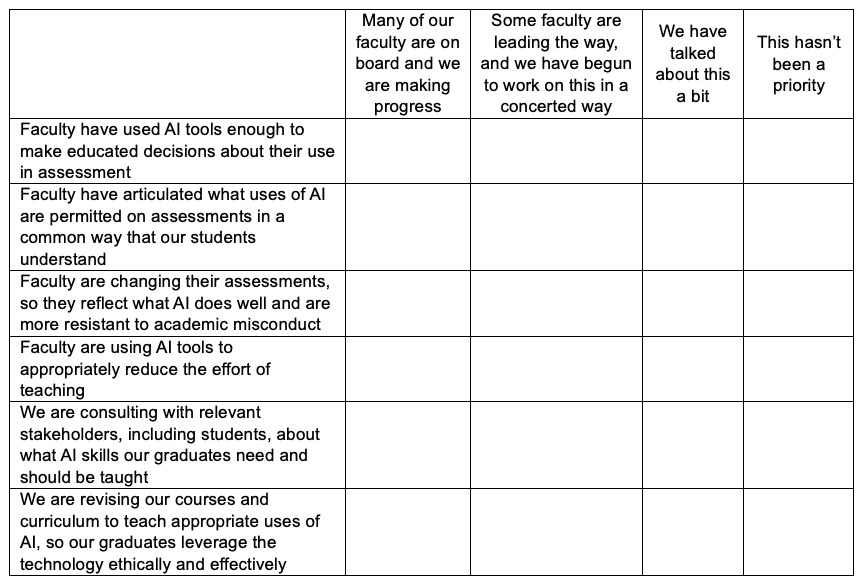

As you prepare to advance this work, we encourage you to self-assess where your department/college/school is currently at using this readiness assessment.

AI readiness assessment for your department/college/school

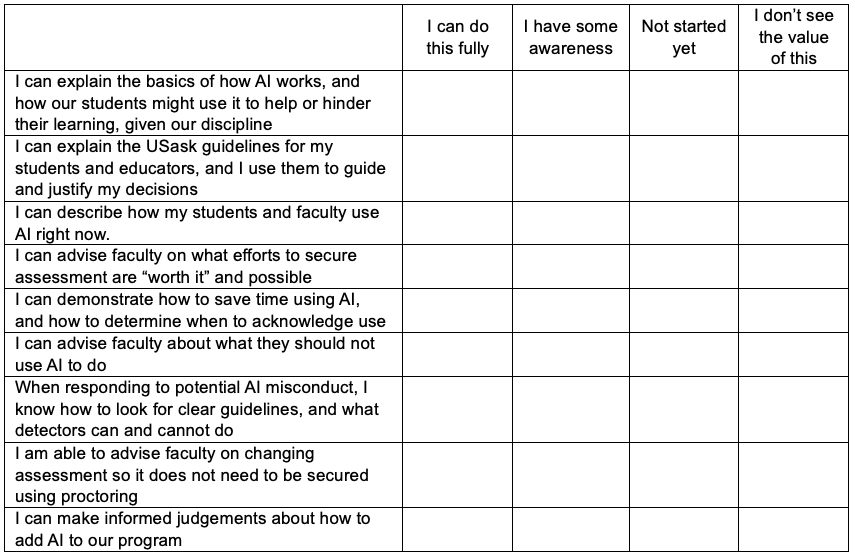

In addition, as you prepare to lead this work, we encourage you to assess your current personal AI readiness.

Personal AI Readiness Self-Assessment for Academic Leaders

Title image credit: Image by Jamillah Knowles & Reset.Tech Australia / © https://au.reset.tech/ / Better Images of AI / Detail from Connected People / CC-BY 4.0